|

NOTES AND EXTRACTS

ON THE HISTORY OF THE

LONDON

& BIRMINGHAM

RAILWAY

ADDENDA

――――♦――――

TIMELINE

of some of the events referred to in the preceding narrative.

|

YEAR |

EVENT |

|

1603 |

The earliest record of

a

wagonway, built by Huntingdon Beaumont to

convey coal from his mines at Strelley (to the west Nottingham) to Wollaton,

a distance of some two miles. |

|

1676 |

“Among the rest of the ‘rare engines’ introduced by

master Beaumont into the coal trade, one was ‘Waggons with one horse

to carry down coales from the pits to the staiths to the river.’

Lord Keeper Guilford, in 1676, thus describes them: ‘The manner of

the carriage is by laying rails of timber from the colliery down to

the river, exactly straight and parallel; and bulky carts are made

with four rowlers, fitting these rails, whereby the carriage is so

easy, that one horse will draw down four or five chaldron of coals,

and is an immense benefit to the coal merchants.’” |

|

1698 |

[2nd July] Thomas Savery patents an

early steam engine (thermic siphon), “A new invention for raising

of water and occasioning motion to all sorts of mill work by the

impellent force of fire, which will be of great use and advantage

for drayning mines, serveing townes with water, and for the working

of all sorts of mills where they have not the benefitt of water nor

constant windes.” In 1702 Savery describes the machine in his

book The Miner's Friend; or, An Engine to Raise Water by Fire. |

|

1707 |

Dionysius Papin

publishes The New Art of Pumping

Water by Using Steam. |

|

c. 1712 |

Thomas Newcomen invents the atmospheric engine, the first practical

device to harness the power of steam to produce mechanical work. |

|

c. 1730 |

Tramway wagons begin to

acquire iron wheels. |

|

1758 |

Charles Brandling’s wagonway opened,

linking his collieries at Middleton with Leeds. It is credited

with being the world’s oldest continuously working line. |

|

c. 1770 |

Iron re-enforced track. |

|

c. 1790 |

All iron rails. |

|

c. 1785 |

Iron edge rails,

requiring the use of flanged wheels, first reported to be in use. |

|

c. 1789 |

William Jessop uses

‘fish bellied’ edge rails on a public railway at Loughborough. |

|

1781 |

[9th June] Birth of George Stephenson. |

|

1801 |

The Surrey Iron Railway

(Wandsworth to Croydon) becomes the first railway company to be authorised

by Act of Parliament. |

|

1801 |

[28th December]

Trevithick’s Puffing Devil ―“The travelling engine took its departure from Camborne Church Town

for Tehidy on the 28th of December, 1801, where I was waiting to

receive it. The carriage, however, broke down, after travelling very

well, and up an ascent, in all about three or four hundred yards. The carriage was forced under some shelter, and the parties

adjourned to the hotel, and comforted their hearts with a roast

goose, and proper drinks, when, forgetful of the engine, its water

boiled away, the iron became red hot, and nothing that was

combustible remained, either of the engine or the house.” |

|

1803 |

Opening of Surrey Iron

Railway. |

|

1803 |

[16th October] Birth of Robert Stephenson. |

|

1804 |

Trevithick’s locomotive

hauls wagons on Merthyr Tydfil Tramroad. |

|

1812 |

The Kilmarnock & Troon

Railway becomes the first railway to be opened in Scotland. It was

the first railway (in fact a plateway using L-shaped iron plates) in

Scotland to obtain an authorising Act of Parliament; to use a steam

locomotive; to carry passengers; and the River Irvine bridge, Laigh

Milton Viaduct, is the earliest railway viaduct in Scotland. |

|

1812 |

The Middleton Railway,

Leeds, becomes

the site of the world’s first rack railway and of the first

commercially viable steam locomotive built by John Blenkinsop. |

|

1813 |

[March 13th] Mr.

William Hedley, viewer to Mr Blackett, of Wylam, took out a patent

for a locomotive engine, which succeeded so well as to draw eight

loaded wagons at the rate of four or five miles an hour, and

completely superseded the use of horses. It would thus appear that

to Mr Hedley belongs the honour of first making the locomotive

engine of practical use. This engine has been in constant use until

recently, when it was removed to the Patent Museum at Kensington. |

|

1813 |

[July 27th] This day

Stephenson’s engine was placed upon the Killingworth Colliery

Railway, and on an ascending gradient of 1 in 450 it drew eight

loaded wagons of thirty tons weight at the rate of four miles per

hour. By the application of the steam blast the power of the engine

was doubled. |

|

1813 |

[September 2nd] One

of Blenkinsopp’s engines was placed upon the Kenton and Coxlodge

Railway; it drew sixteen loaded chaldron wagons (a weight of about

seventy tons) about three miles per hour. The boiler of the engine

shortly blew away, and was not replaced. |

|

1815 |

Stephenson patents an

improved locomotive engine. |

|

1820 |

[12th February] The

first promoters’ meeting of the Stockton and Darlington Railway. |

|

1821 |

[April 19th] Upon

this day occurred the interview between the late Edward Pease, the

Father of Railways, and George Stephenson, relative to the making of

the Stockton and Darlington Railway, for which an Act was this year

obtained, but the first rail was not laid until the 23rd of May,

1822. |

|

1822 |

[November 18th] On

this day the Hetton Colliery Railway was opened, and the first coals

from the colliery were shipped. Five of George Stephenson's patent

travelling engines were used on the railway, of which Robert

Stephenson his son was resident engineer. |

|

1824 |

[September 25th]

Prospectus of Liverpool & Manchester Railway Company issued. |

|

1825 |

[September 27th] The

Stockton and Darlington Railway, of which George Stephenson was

engineer, was opened for twenty-five miles in length, from Stockton

to Witton Park. In the early days of this railway the passengers

were conveyed in ordinary coaches mounted upon railway wagon wheels.

Upon Sundays it was usual for the “Friends” residing at Shildon to

go to Darlington in a car drawn by a horse along the line. |

|

1829 |

Stephenson’s Rocket

(separate firebox, multi-tubular boiler, inclined cylinders, sprung

axles) wins the Rainhill Locomotive Trials. |

|

1830 |

[15th September]

Opening of the Liverpool and Manchester Railway, Britain’s first

inter-city railway. |

|

1830 |

[November]

Stephenson’s first set of deposited plans

for the London and Birmingham Railway show its London terminus to be

situated to the north of Hyde park, west of the Edgeware Road and

adjacent to the confluence of the Grand Junction and Regent’s

canals. |

|

1832 |

[July] First attempt to obtain an Act of Parliament fails on the

resolution of the Earl of Brownlow. |

|

1833 |

[6th May] Acts

authorising the construction of the London and Birmingham Railway,

and the Grand Junction Railway, receive the Royal Assent. |

|

1834 |

[May] First construction contracts let, covering the Primrose Hill,

Harrow and Watford sections of the line. |

|

1835 |

[17th July] Tunnel

collapse at Watford kills ten men. |

|

1835 |

[31 August] The Great Western Railway Act receives the Royal Assent. |

|

1835 |

[3rd July] Act

authorising the extension of the London and Birmingham Railway from

Camden Town to Euston Grove receives the Royal Assent. |

|

1835 |

[9th December] W. and

L. Cubitt awarded the contract to build the Euston Extension. |

|

1836 |

[July] A tender from

the engineering firm of Maudslay, Sons and Field accepted to supply

the Camden winding engines. |

|

1837 |

George Carr Glyn

(later the 1st Baron Wolverton) becomes the second Chairman of the

London and Birmingham Railway. He later became Chairman of the

London & North-Western Railway Company, a position he held until

1852. The Railway’s first Chairman was Isaac Solly, was

declared bankrupt during the 1837 banking crisis. |

|

1837 |

[10th June] Cooke and

Wheatstone patent a telegraph system which uses a number of needles

on a board that could be moved to point to letters of the alphabet.

The patent recommended a five-needle system, but any number of

needles could be used depending on the number of characters it was

required to code. |

|

1837 |

[4th July] The Grand

Junction Railway commences services between Birmingham and

Warrington, from where Liverpool and Manchester could be reached via

the Warrington and Newton Railway. The services operated originally

from a temporary terminus at Vauxhall, but when the Lawley Street

viaduct was completed in 1839, services were extended to the London

and Birmingham terminus at Curzon Street. |

|

1837 |

[20th July] The London

and Birmingham Railway commences services between Euston Grove and

Boxmoor (Hemel Hempstead). |

|

1837 |

[25th July] A

four-needle Cooke and Wheatstone telegraph system installed between

Euston and Camden Town is demonstrated successfully in the presence

of Robert Stephenson. Although Stephenson is in favour, the system

is not taken up by the London and Birmingham Railway Company. |

|

1837 |

[16th October] The

London and Birmingham Railway extends services to Tring. Also in

October, Thomas Townshend, contractor for the Tring Cutting,

abandons the contract. |

|

1838 |

[January] The

Travelling Post Office is introduced on the Grand Junction Railway

using a converted horse-box. The last Travelling Post Office

services were ended on 9th January 2004. |

|

1838 |

[9th April] The London

and Birmingham Railway extends services to Denbigh Hall (nr.

Wolverton) and commences services between Birmingham (Curzon Street)

and Rugby. The intervening 38-mile gap is bridged by a

stagecoach/omnibus services. Also in April, work is completed

on the Wolverton Viaduct. |

|

1838 |

[June] Work completed

on the Kilsby Tunnel. |

|

1838 |

[10th August] The

Special Constables Act is passed

requiring railway and other companies to bear the cost of constables

keeping the peace near construction works. |

|

1838 |

[14th August] The

Railways (Conveyance of Mails) Act 1838 (1 & 2 Vict. c. 98) ― an Act

requiring the transport of the Royal Mail by railways at a

standardised fee ― receives the Royal Assent. |

|

1838 |

[20th September] The

London and Birmingham Railway is opened throughout. |

|

1839 |

Electric telegraph on the Cook & Wheatstone system laid down along a

13-mile section of the Great Western Railway, between Paddington and

West Drayton. |

|

1839 |

First railway hotels opened at Euston. The

Victoria Hotel offered basic sleeping accommodation and coffee house

services, meant for working-class men. The Euston Hotel offered a

full service, catering to middle class families and first-class

travellers. |

|

1839 |

Birmingham and Derby

Junction Railway open a station at Hampton (aka Derby Junction) to

provide connections with London and with Birmingham services. |

|

1839 |

[10th June] The

Aylesbury to Cheddington Railway, the UK’s first branch line,

opened. |

|

1839 |

[December] Cooke and

Wheatstone’s telegraph first applied to block signalling on the

Great Western Railway between Paddington, West Drayton, and Hanwell. |

|

1840 |

A hotel is opened on

the northern side of the Curzon Street terminus at Birmingham. The

hotel closed when Queen’s Hotel was opened next to New Street

station. |

|

1840 |

The

Midland Counties Railway to Rugby opened. |

|

1840 |

[10th August] Regulation of Railways Act comes into force:

1. No railway to be

opened without notice;

2. Returns to be made by railway companies;

3. Appointment of Board of Trade inspectors;

4. Railway byelaws to be approved by the Board;

5. Prohibition of drunkenness by railway employees;

6. Prohibition of trespass on railways. |

|

1841 |

[30th June] Great

Western Railway main line opened between London and Bristol. |

|

c.

1842 |

Semaphore signals first

used on British railways on the London and Croydon Railway at New

Cross. |

|

1842 |

[2nd January] The

Railway Clearing House (RCH) commences operations in premises at 111

Drummond Street, opposite Euston Station. Owing to expansion, the

RCH moved to larger purpose-built premises in Seymour Street

(renamed Eversholt Street in 1938) in 1849, which remained its

headquarters for the rest of its existence. The RCH was dissolved as

a corporate body on the 8th April 1955, its residual functions then

being taken over by the British Transport Commission. |

|

1842 |

[13th June] Queen

Victoria makes her first railway journey from Slough to Paddington

on the Great Western Railway. The locomotive to do the honours was

Phlegethon, a GWR Firefly-class locomotive built at the Round

Foundry, Leeds, the same factory that had 30 years previously built

the first commercially successful locomotives for the Middleton

Railway. |

|

1842 |

[August] Troops are

carried by train from Euston to suppress industrial unrest in the

Midlands and the North of England, the first recorded use of the

railway in Great Britain by the military. |

|

1843 |

Sections of the

retaining wall on the Camden Incline being forced forward by

waterlogged London clay. |

|

1844 |

[9th August] The

Railway Regulation Act (“Gladstone’s Act” ) required that:

1. One train with

provision for carrying third-class passengers, should run on every

line, every day, in each direction, stopping at every station.

(These are what were originally known as “Parliamentary” or

“Government” trains.)

2. The fare should be 1d. (½p) per mile.

3. Its average speed should not be less than 12 miles per hour (19

km/h).

4. Third-class passengers should be protected from the weather and

be provided with seats. |

|

1844 |

The Coventry to Leamington railway opened,

initially linking the City with Milverton, but in 1851 the line was

extended into Leamington Spa. |

|

1844 |

[November] Queen

Victoria makes her first train journey on the London and Birmingham

Railway, travelling from Euston to Weedon in Northamptonshire |

|

1845 |

Blisworth to

Peterborough via Northampton line opened. |

|

1846 |

[16th July] The London

& Birmingham Railway, the Grand Junction Railway and the Manchester

& Birmingham Railway amalgamate to form the London & North Western

Railway (L&NWR). The amalgamation was prompted in part by the Great

Western Railway’s plans for a railway north from Oxford to

Birmingham. The L&NWR initially had a network of approximately 350

miles, connecting London with Birmingham, Crewe, Chester, Liverpool

and Manchester. |

|

1846 |

[18th August] The

Railway Regulation (Gauge) Act establishes the national standard of

4ft 8½ inches (1,435 mm) for

Great Britain, and 5 feet 3 inches (1,600 mm) for Ireland. The final

elimination of the broad gauge came in May 1892, when the entire

line between London and Penzance was converted to standard gauge

during a single weekend. |

|

1847 |

[22nd September] The

Railway Clearing House decrees that “GMT be adopted at all

stations as soon as the General Post Office permitted it”. |

|

c. 1847 |

First locomotive

turned out at Wolverton Works. Some

160 locomotives are believed to have been built at the Works, the

last in 1863 when production was centred on Crewe. |

|

1848 |

[12th August] Death of George Stephenson. |

|

c. 1855 |

The L&NWR first use

the two-mile telegraph signalling system on the former London and

Birmingham Railway. |

|

1859 |

A third line, used

mainly for goods traffic, is added between Willesden and Bletchley. |

|

1859 |

[12 October] Death of Robert Stephenson. |

|

1863 |

The Metropolitan

Railway Carriage and Wagon Company Ltd. is formed as the successor

to Messrs. Joseph Wright and Sons of London. |

|

1875 |

Northampton Loop

opened. |

|

1876 |

A fourth track is laid between Willesden and Bletchley. |

|

1889 |

Following the Armagh

rail disaster on 12th June 1889, the Regulation of Railways Act (52

& 53 Vict. c. 57) makes the use of the absolute block signalling

system mandatory on passenger carrying railways. |

|

1921 |

The Railways Act ―

generally known as “the Grouping” ― enacted in an attempt to stem

the losses being made by many of the country's 120 railway

companies. Four large railway companies are formed; The Great

Western Railway; The London, Midland and Scottish; The London and

North Eastern; and The Southern Railway. |

|

1923 |

The Railways Act

takes effect on the 1st January. The former London and

Birmingham Railway becoming a constituent of the London, Midland and

Scottish. |

|

1948 |

[1st January]

“British Railways” comes into existence as the business name of the

Railway Executive of the British Transport Commission (BTC), and

takes over the assets of the Big Four. The railways are now

state owned. |

|

1967 |

Completion of the

scheme to electrify (25kV, 50Hz) of the former London and Birmingham

Railway. |

|

2012 |

[January] The

construction of phase 1 of a new railway linking London and

Birmingham is approved. Construction is set to begin in 2017,

with an indicated opening date of 2026. Stephenson and his

team did the job rather quicker. |

――――♦――――

|

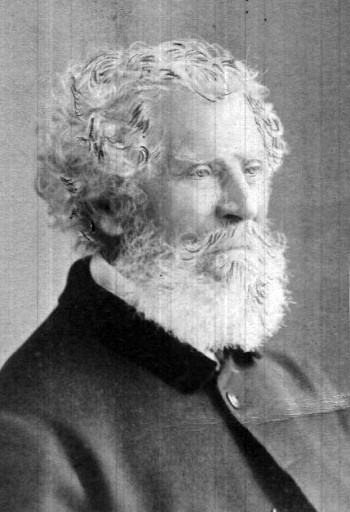

A note about the artist

JOHN COOKE BOURNE

Having reproduced a number of Bourne’s drawings, something needs to

be said about the artist.

The London and Birmingham Railway was built on the eve of

photography; had the line been constructed five years later ― or the

first two photographic processes (Daguerreotype and Calotype) invented five years earlier ― we might now be able to

view and admire photographic images of the line’s

stations and civil engineering structures as they appeared to

Roscoe, Freeling, Osborne and other authors of the early railway travel

guides. Photographs are not available until

some years after the line’s opening, by which time much had changed,

particularly its stations. Thus accurate depictions of the London

and Birmingham Railway during and immediately following its

construction are only available in drawings, and particularly those of the artist and

engraver John Cooke Bourne (1814-95).

Bourne is something of an enigma, for there are periods of his

life, particularly his later years, in which he appears to have

produced nothing, and during which nothing is known of him. [11] What

is known, is that he was a gifted

draughtsman and that he began a series of sketches and watercolour

drawings of the Railway during its construction, which attracted

critical acclaim from John Britton, author and patron of the arts,

who subsequently became Bourne’s sponsor:

LONDON

AND BIRMINGHAM RAILWAY.

Historical and Descriptive Accounts op the Origin, Progress, General

Execution, and Characteristics op the LONDON

and BIRMINGHAM RAILWAY.

Folio. 1838-9.

“Some beautiful drawings of this Railway were made, con amore,

in the year 1838, by Mr. John C. Bourne, as studies from nature. They were submitted to Mr. Britton, who suggested the expediency of

their being published. The great cuttings, embankments, and tunnels,

on the London and Birmingham Railway, were, at the time referred to,

matters of great novelty and absorbing interest to the inhabitants

of the metropolis; and it appeared therefore certain that the beauty

of Mr. Bourne’s drawings, and the popularity of the subject, would

ensure success in their publication.

On considering the best mode of multiplying the drawings, that of

tinted lithography was adopted, as best calculated to preserve the

spirit and character of the originals, without reducing them in

size. Although Mr. Bourne had not previously made any drawings on

stone, he was eminently successful even in his first efforts; and

the whole of the series (thirty-seven in number) were thus executed

by himself. The prints were published in four periodical parts, at

one guinea each (super-royal folio). On the completion of the work,

a general Historical and Descriptive Account of the Railway,

occupying twenty-six closely-printed pages, was written by Mr.

Britton. It comprises remarks on, — ‘Past and present modes of

travelling. Public roads. Stage Coaches, Turnpikes, Mails, Canals,

Steam Boats, Locomotive Engines, History of the Railway System, and

of the origin and formation of the London and Birmingham Railway. Brief Descriptive account of that line, with its Stations, Viaducts,

Tunnels, and Embankments, and notices of the Towns, Villages, Seats,

&c., upon the line and its immediate vicinity.’ In the drawings, the

great Embankments, Cuttings, Tunnels, and other Railway works are

represented; some in their completed state, but most of them as they

appeared in various stages of their formation; and the artist has

delineated some extraordinary scenes and objects, in which

innumerable workmen, and gigantic machinery, appear to be in active

operation.

Mr. Bourne has since produced a series of drawings of the Great

Western Railway (published by C. F. Cheffins), in which all the

objects are represented in their finished state. Mr. Britton wrote a

Prospectus, &c., for that work, but was not otherwise connected with

it.”

The Auto-biography of John

Britton, Part II. (1849).

In 1847, Bourne travelled to Russia with the civil engineer Charles

Blacker Vignoles. Vignoles had been commissioned to design and

build the Nicholas Chain Bridge over the River Dnieper in Kiev,

Bourne having previously produced an artist’s impression of the

intended bridge in watercolour. While in Russia, Bourne also created

images using the early daguerreotype photographic process. Despite

living for another forty years, very little is known of his life of

work, and he probably died with little, if any, appreciation of how

important his early railway drawings ― particularly those of the

London and Birmingham Railway under construction ― would

eventually become.

――――♦――――

NAVVIES AS THEY USED TO BE

from

Household Words

Vol. XIII.,

19th January 1856.

IN the year one

thousand eight hundred and thirty-four, having completed my

education at an academy near Harrow, wherein I had spent six years

of the sixteen to which I had attained, I returned to my native

village, and declared my wish to be an engineer. We lived in a

remote corner of the county of Hertford. Everywhere railways were

almost untried innovations, therefore, my worthy guardian, when I

told him that I meant to be an engineer, said that he pitied me from

his heart, and begged that I would banish the thought instantly.

I did not heed his counsel. In the autumn previous to my leaving the

school, situated, as I said, near Harrow, the works of the London

and Birmingham Railway had been commenced close to its academic

groves. Opportunity had thus directed my attention towards

engineering works. Even a little knowledge was thus gained which had

become the stimulus to further acquisitions; so that I bought for

myself Grier’s Mechanics’ Calculator, and Jones on Levelling,

studied them in leisure hours, made fresh observations as to the

progress of the works whenever I could manage to climb over the

playground wall; and when I returned home, had got so far that I

could keep a field-book, reduce levels, compute gradients, and

calculate earthworks with tolerable accuracy. I left school resolved

to be an engineer.

My guardian was equally resolved that I should not have my own way

in the matter; so I rose early one morning in the month of March,

eighteen hundred and thirty-five, packed up a change of linen and an

extra pair of trousers, with my Grier in a handkerchief, and with

but a few shillings in my pocket, set off for the nearest railway

works. There I hoped to obtain employment, and, by beginning at the

beginning, to follow upon, their own road the Smeatons, Stevensons,

and Brunels. I tramped, therefore, to Boxmoor; and reaching the

unfinished embankment at that place, after a walk of some thirty

miles, footsore and weary, I went boldly upon the ground and asked

for work. I don’t know what the men — the gaffers, as they were

called, thought of me. One told me that, “I looked too much like a hap’porth of soap after a hard day’s wash to be fit for much;”

another asked me whether I had made up my mind not to scratch an old

head; but at last my perseverance in application was rewarded with a

driver’s job, at twelve shillings a-week wages. I was to drive a

horse and truck full of earth along the temporary rails of the

embankment to the end of it, where the truck was tipped, and its

contents shot out to serve towards the further extension of the

bank.

I was a driver for more than a fortnight, during which time my

clothes were torn to ribbons. In the course of my third week I did

that which I had seen other unfortunates do, — I drove horse and

truck together with the earth, over the tip-head.

Forfeiting my wages and my situation, I trudged to Watford tunnel,

which I reached on the same evening; and, next morning at day-break

I was descending one of the great shafts, a candidate for

subterranean labour. I rose in the world afterwards; but my rise

dates from this descent.

The man to whom I had engaged myself was a sub contractor of the

fourth degree — Frazer, by name, a thorough Yorkshireman — who never

spoke without an oath, was never heard even to call man, woman, or

child by Christian name; whose only varieties of expression were

that when he was in a bad humour he swore at others, when in a good

humour he cursed himself. My job under this man, was

bucket-steering. Placed upon the projecting ledge of a scaffold some

eighty feet above the level of the rails in the tunnel, and one or

two hundred feet below the surface of the earth, while bricklayers,

masons, and labourers were busy upon the brickwork of the shaft

above, below and round me, while torches and huge fires in cressets

were blazing everywhere. I was, in the midst of the din and smoke,

to steer clear of the scaffold the descending earth-buckets one of

which dropped under my notice every three minutes at the least. This

duty demanding vigilant attention, I had to perform for an unbroken

shift (as it was termed) of six hours at a stretch.

“Look thou,” said Frazer with an oath, when giving me instructions,

“you just do like this.” I was to clasp a pole with my left arm,

hang over the abyss, and steady the buckets with a stick held out in

my right hand. “Do like this,” he repeated, swearing, “but mind, if

you fall, go clean down without doing any mischief. Last night I’d

to pay for a new trowel that the little fool who was killed

yesterday knocked out of a fellow’s hand.” The little fool was the

poor lad whom I replaced, and as I afterwards learned, was a runaway

watchmaker’s apprentice out of Coventry, who had been worked for

three successive shifts without relief, and who had fallen down the

shaft from sheer exhaustion. And, before I knocked off my first

shift, I was not surprised at his fate. I was so thoroughly

exhausted that Frazer put me into the bucket, and gave orders to a

man to bear a hand with me to Sanders’s fuddling crib, and let me

have a pitch in for an hour, and a pint.

Sanders’s fuddling crib was a double hovel, situated nearly at the

foot of the shaft. The “pitch in” with which I was to be indulged

was a lie-down on a mattress, of which there were several; nearly

all of them occupied by men and boys more or less exhausted. I slept

for six hours, and awoke refreshed; but, no sooner was it discovered

that I was awake, than I was told to “scuttle out,” which I did

quickly, and my bed was instantly filled by another over-wearied

worker. “Now get your pint,” said the old wooden-legged man who had

charge of this sleeping accommodation. I was ushered into the other

section of the hovel in which there were some thirty men drinking,

smoking and swearing in true navigator style, before a bar

established for the sale of beer. I did not get my pint, for I

eschewed beer; but bargained it away with a man for a drink of

coffee from his bottle. It was strong and warm, for the bottle had

been standing on the hot stone hearth; the very smell of the coffee

was inspiriting, and I was on the point of putting the bottle to my

lips when it was dashed from my hands by a huge fellow, who rushed

past us to the fire, exclaiming,

“Hist! hist! Red Whipper’s a gwain to fight the devil!”

I looked round. Seated on one of the benches about half-way down the

hut was a man who had fallen asleep over his beer. He wore a loose

red serge frock and red night-cap, the peak of which appeared

through a newspaper which had been thrust over his head, and hung

down to his knees. A momentary hush prevailed; when the man who had

knocked down my coffee, returning with a light, set fire to the

paper. Red Whipper was instantly enveloped in flame, and started

from his sleep in fierce alarm, throwing his arms about him like a

madman. This joke was called fighting the devil. It led to a general

scuffle, in the midst of which I made my escape into the wider,

though more reasonable, turmoil of the tunnel. There was no day

there and no peace: the shrill roar of escaping steam; the groans of

mighty engines heaving ponderous loads of earth to the surface; the

click-clack of lesser engines pumping dry the numerous springs by

which the drift was intersected; the reverberating thunder of the

small blasts of powder fired upon the mining works; the rumble of

trains of trucks; the clatter of horses’ feet; the clank of chains;

the strain of cordage; and a myriad of other sounds, accordant and

discordant. There were to be seen miners from Cornwall, drift-borers

from Wales, pitmen from Staffordshire and Northumberland, engineers

from Yorkshire and Lancashire, navvies — Englishmen, Scotchmen, and

Irishmen — from everywhere, muck-shifters, pickmen, barrowmen,

brakes-men, banksmen, drivers, gaffers, gangers, carpenters,

bricklayers, labourers, and boys of all sorts, ages and sizes; some

engaged upon the inverts beneath the rails, some upon the drains

below these, some upon the extension of the drifts, some clearing

away the falling earth, some loading it upon the trucks, some

working like bees in cells building up the tunnel sides, some upon

the centre turning the great arches, some stretched upon their backs

putting the key-bricks to the crown — all speaking in a hundred

dialects, with dangers known and unknown impending on every side;

with commands and countermands echoing about through air murky with

the smoke and flame of burning tar-barrels, cressets, and torches.

Such was the interior of Watford tunnel. There were shops in it,

too: not only beer or fuddling-shops, but tommy-shops. The navvy

knows that he is a helpless being if he cannot get his tommy; and

this word, which comprehends all animal supplies (drink is wet tommy),

signifies beef, bacon, cheese, coffee, bread, butter, and tobacco.

My job as bucket-steerer did not last long; for the drift north of

the tunnel being soon cut through, no more earth was taken up the

shaft; it was all carried out through Hazlewood cutting, to be used

in the formation of the long embankment between Hunton Bridge and

King’s Langley.

Frazer, who told me that I was a handy lad, did not discharge me

altogether, but shifted me to a gang of regular navvies in the

tunnel. With my first fortnight’s wages I had got me a suit of new

moleskin and a pair of highlows; now, therefore, I had only to buy

pick and shovel, and my equipment was complete. My hands had become

coarse, my face was sunburnt, and my hair shaggy. What matter? I

felt a hearty pride in myself, and my prospects.

The gang I joined consisted of some forty men, each of whom bore a

nickname. There were Happy Jack, Long Bob, Dusty Tom, Billy-goat,

Frying-pan, Red-head, and the rest with names more or less

ludicrous. For myself, my new clothes and tools entitled me to the

style of Dandy Dick. I was fined two gallons footing, which I paid;

and was put to work with a lad, whom they called Kick Daddy, in

clearing out a trench.

With this gang I worked steadily and punctually, making no enemies

and one friend. This friend was Canting George; a tall, thin,

hard-lined, stern-featured, middle-aged man, commonly sneered at by

his fellows because he was said to be religious; though I never knew

him attempt to make a proselyte, or interfere at any time by word or

deed with drinking, swearing, quarrelling, or fighting. His only

cause of offence, as far as my observation extended, was, that he

was never at any time drunk or riotous himself. Canting George was a

native of an obscure spot in Warwickshire. He was an extreme

Calvinist, and miserably ignorant, for he could not even read; yet

he possessed very good reasoning powers.

My education having more than once betrayed itself, this man, who

had a thirst for knowledge, fastened himself upon me. But his

friendship was not altogether selfish; for I soon owed much to his

protection. Bullhead, as our ganger was called, was a surly brute,

and Canting George frequently saved me from his violence. But for

him, too, instead of continuing to live at my lodgings in a clean

cottage at Hunton Bridge, I should have been compelled to live in

the shanty with the rest of the gang; and rather than have done

that, I should have given up the effort to make myself an engineer

altogether.

The shanty was a building of stone, brick, mud, and timber, and

roofed partly with tile and partly with tarpaulin. It consisted of a

single oblong room, and stood upon a piece of spare ground near the

tunnel mouth; another nearby shanty tenanted by another of Frazer’s

gangs, stood upon the high ground just above; and between both,

under a single roof, were Frazer’s office and his tommy-shop.

Almost every gang of navvies — and there were sixty, at least,

employed upon the tunnel — was thus lodged; so that there were

several of these dens of wild men round about the works. The

bricklayers, masons, mechanics, and their labourers were distributed

among the adjacent population, carrying disorder and uproar wherever

they went. I will not attempt to say what might have been the social

aspect of affairs in the neighbourhood of the line if the hordes of

reckless navigators had been lodged in the same way. Their own

arrangement was made, not on moral grounds, entirely by the men and

their gaffers (the sub-contractors) to suit their own convenience;

for the navvie does not like to reside far from his work.

The domestic arrangements of the navigators’ shanties were presided

over by a set of blear-eyed old crones, of whom there was one to

each gang. They were expected to cook, make the beds, wash and mend

the clothes of their masters; who beat them fearfully whenever the

fancy of any one or more of their rough lords and masters inclined

to that refreshment. In all the obscenity and blasphemy they bore

their part; in the fighting they also lent a hand. With features

frightfully disfigured, with heads cut and bandaged, they made

themselves at home in the midst of everything from which pride and

virtue shrink aghast.

Once only I visited our shanty. I was, in spare hours, teaching

George Hatley to read; and it happened one Sunday morning early in

May that the rain, hindering church attendance, I strolled up to the

shanty to find George; but he was gone out. Old Peg, the presiding

crone, who was then exhibiting two black eyes and a bandaged chin,

told me that he would be back by eleven — it was then past ten; and,

having cursed me in a way intended to be very friendly, she invited

me to wait till he returned. So I sat down on a three-legged stool,

and took a survey of the place.

The door was about midway in one of the sides, having a window on

each side of it, and near one of the windows were a few rude benches

and seats. Of such of my comrades as were up, four or five were

sprawling on these seats, two lying flat upon the earthen floor

playing at cards, and one sat on a stool mending his boots. These

men all greeted me with a gruff welcome, and pressed me to drink. Near the other window were three barrels of beer, all in tap, the

keys of which were chained to a stout leathern girdle, which

encircled old Peg’s waist. Her seat — an old-fashioned arm-chair —

was handy to these barrels, of which she was tapster. The opposite

side and one end of the building were fitted up from floor to roof —

which was low — in a manner similar to the between-decks of an

emigrant ship. In each of the berths there lay one or two of my

mates — for this was their knock-off Sunday — all drunk or asleep. Each man lay with his head upon his kit (his bundle of clothes);

and, nestling with many of the men were dogs and litters of puppies

of the bull or lurcher breed; for a navvie’s dog was, of course,

either for fighting or poaching.

The other end of the room served as the kitchen. There was a rude

dresser in one corner, upon which and a ricketty table was arranged

a very miscellaneous set of plates and dishes, in tin, wood, and

earthenware, each holding an equally ill-matched cup, basin, or

bowl. Against the wall were fixed a double row of cupboards or

lockers, one to each man; these were the tommy-boxes, and below

them, suspended from stout nails and hooks, were several large pots

and pans. Over the fireplace, which was nearly central, there were

also hung about a dozen guns. In the other corner was a large

copper, beneath which a blazing fire was roaring: a volume of

savoury steam was escaping from beneath the lid, and old Peg,

muttering and spluttering ever and anon, threw on more coals and

kept the copper boiling. Now, as I looked at this copper, I noticed

a riddle not particularly hard to solve. Depending over its side,

were several strings, communicating with the interior; and, to each

of these, was attached a piece of wood. Peg, muttering and

spluttering, was continually handling one or more of these

mysteries. I asked her the meaning of them.

“Them!” said Peg, speaking in a broad Lancashire dialect, and taking

a stick in her hand; “why, sith’ee lad — this bit o’ stick has four

nicks in’t — well it’s Billygoat’s dinner: he’s abed yond. Now

this,” taking up another with six nicks, “is that divil Redhead’s,

and this,” seizing a third with ten nicks, “is Happy Jack’s. Well,

thee know’st, he’s got a bit o’ beef; Redhead’s nowt but taters —

he’s a gradely brute is Redhead; an’ Billygoat’s got a pun or so o’

bacon an’ a cabbage. Now thee sees I’ve a matter o’ twenty dinners

or so to bile every day, which I biles in nets; an if I didna’ fix ’em

in this road (manner) I should’na never tell where to find ’em, and

then there’d be sich a row as never yet was heerd on.” Shortly

afterwards Red Whipper came in, bringing with him a leveret. This

was a signal for Peg. His orders to her were, “Get it ready, and put

it in along o’ the rest, and look sharp, or thee’s head may be

broken.” He then took off his jacket and boots and tumbled up into a

berth.

In the course of the month of June, Frazer took more work, and set

on two or three extra gangs of navvies. One of these built a shanty

nearly opposite to the one occupied by my gang. These new-comers

were chiefly Irish, and they had not been there many days before a

row took place, which, while it lasted, brought picks, spades,

shovels, mawls, beetle-cudgels, and every available weapon into

active service. The fight took place on a Saturday evening, about

two hours after pay-time. It was our fortnightly payday; and the men

being well sprung with drink, the affray was desperate. It lasted

for more than an hour; no interruption being offered to the

combatants. Indeed nothing short of military interference could have

quelled such a disturbance. My gang was victorious. But their

triumph was dearly purchased: five of our comrades were shockingly

hacked and disabled. More than a dozen of the Irishmen were mangled,

and one was taken up for dead. The finale of this war was the

burning of the Paddies’ shanty. After this ejectment order was

restored.

Later in the summer occurred that terrible disaster by which upwards

of thirty men, were buried alive by the in-falling of a mass of

earth. Fourteen were not rescued until life was extinct, and the

last body not recovered until after a lapse of three weeks. Of those

who were rescued alive, all, with the exception of one man,

sustained more or less of corporeal injury — fractures, contusions,

and bruises. This man, who owed his rescue to having been at work

beneath some shelving planks when the earth fell in, was taken out

crazed, and died shortly after a raving madman. The causes assigned

for the accident were conflicting; and, as is usual in such cases,

each party did their best to fix the blame upon the other — the

engineers upon the contractors, these upon their sub-contractors,

and these again upon those beneath them. I believe that the disaster

was really attributable to a foreman of bricklayers, who madly, and

against orders, drew away the centering of some newly-turned arches;

the earth followed; and the doomed men beneath — presuming the cause

I have given to be the right one—became the victims of a drunken

man’s temerity.

The scene was terrible. Above yawned an abyss, down which huge trees

had been carried, for it was woodland here above the tunnel; the

trunks of many had been snapped like sticks, and the roots of some

were branching up into the air. Below, on either side of the mass,

were gangs of brave, daring men — the navvie is a bold fellow when

danger is to be faced — endeavouring to work their way through it. Day and night, for one-and-twenty days, these labours unremittingly

continued, until at length the body of the last victim was found.

George Hatley, having got on with his studies, informed Frazer, who

was little better than no scholar at all, of his new capabilities. With the jealousy peculiar to ignorance, Frazer had never been able

to tolerate the idea of having a well-dressed or well-educated clerk

in his employment, and his sphere of operations had for that reason

been limited to works under his own supervision. Now, however, he

felt that if he could get another contract on some other portion of

the line, George could be safely put in charge of it. Frazer

accordingly put in for, and obtained a contract to carry a portion

of the drift through Northchurch tunnel; over this job he appointed

George his gaffer, and George then got me to be appointed his

assistant and time-keeper. So to Northchurch tunnel we went, early

in October; and, under the directions of the engineers, opened the

drift at the north end of the tunnel; sinking a shaft about midway

on our length, which was, I think, about one hundred and fifty

yards. By the middle of November we had six gang of navvies at work

— each from thirty to forty strong; and Frazer, who came down twice

a week to give directions and watch progress, never before, as I

believe, had felt himself so great a man. He purchased a new suit of

clothes, displayed a watch-guard; and, but for his vulgar mind and

manners, would have passed for a gentleman.

The men at Northchurch were, if possible, a more desperate and

licentious set than those whom I had known at Watford tunnel. They

had just come off a job on the Birmingham canal, and at first called

themselves muck-shifters and navigators, holding the abbreviation "navvie"

in contempt. They were not lodged in shanties, but in surrounding

villages and in the neighbouring town of Great Berkhampstead.

The soil through which we were carrying the drift of Northchurch

tunnel was of a most treacherous character, and caused many

disasters. Despite every precaution, the earth would at times fall

in, and that, too, when and where we least expected. Thus, in the

fifth week of our contract, notwithstanding that our shoring was of

extra strength and well strutted, an immense mass of earth suddenly

came down upon us. This came from the tapping of a quicksand. One

stroke of a pick did it. The vein was shelving and the sand, finding

a vent, ran like so much water into the open drift; which was of

course speedily choked up. George Hatley was at once on the spot;

and, under his directions efforts were promptly made to clear away

the sand, so that the shoring should be re-strengthened if possible

before the earth above (deprived of the support afforded by the

sand) should collapse. The most strenuous efforts were made in vain.

There came a low rumbling, like the distant booming of artillery,

then followed crashes louder than the thunder, startling us from our

labour; and, while we were hurrying away, down came the whole mass

of earth, masonry, timber, and sand, crushing five men under it.

Of these men three were dug out alive, and removed — terribly

mangled — to the West Herts Infirmary; the other two were found

dead. They belonged to a gang, of which one Hicks or Bungerbo, was

ganger. I have described Frazer as a man terribly profane, but Hicks

was in this matter his master. These were the first lives lost in Northchurch tunnel, and Hicks was overjoyed to think that they

belonged to his own gang. He looked forward to the funeral; and,

having organised a subscription of a shilling per head throughout

all the gangs in the tunnel — which subscription realised twenty

pounds — five pounds were set apart to pay for burial of the dead,

and the rest was reserved to be spent in rioting and drunkenness.

The funerals took place on the afternoon of the Sunday following the

disaster, in the churchyard of Northchurch parish. The procession

was headed by Hicks, who walked before the coffins; behind followed

about fifty navvies, all more or less drunk, and the rear was

brought up by a host of stragglers, and country girls, the

companions of the navvies. There were no real mourners; the

unfortunate men being strangers in the district, and the residences

of their friends unknown. It was about half-past two o’clock when

the train reached the gates of the churchyard. At the church-door

the officiating minister, observing the condition of the men, wisely

ordered the church to be closed, and proceeded to lead the way to

the grave. Hicks took umbrage at this, and threatened to break the

door open; but as this was not seconded among his men, he told them

to put the coffins on the ground, and let the parson do all the

business himself. But the men hesitated, the sexton protested, and

at length the grave was reached. Here Hicks found fresh cause for

offence. It was a single grave, and he said (which was untrue) that

separate graves had been paid for. When this was disproved, he

objected that the one grave was not deep enough, and ordered two of

his men to jump in and dig it to Hell. The men jumped in as ordered,

one had the sexton’s pickaxe, the other the spade, and in little

more than ten minutes the grave was ten feet deeper. Still the men

dug on, and continued their labour, till they could no longer throw

the earth to the surface.

Then rose the question, how were they to get out? The sexton’s short

ladder was useless, for the grave was at least twenty-feet deep. Hicks settled the matter by calling for

“the ropes!” “What ropes?” “The coffin ropes.” These were brought and lowered to the men. With

a loud hurrah they were drawn up, and the clergyman was told to “go

on.”

The good man, pale and terrified, incoherently hurried through the

service, closed the book, and was gathering up his surplice for a

precipitate departure, when Hicks grasped him by the collar and,

with fearful imprecations, demanded a gallon or two of beer, “for,”

he said, “you do not get two of ’em in the hole every day.” Then

followed an atrocious scene. A crowd had collected in the

churchyard, and several of the villagers came forth to the rescue of

their curate, who narrowly escaped uninjured. A desperate fight,

during which one or two men were thrown into the open grave,

terminated the affair.

This revolting outrage was not allowed to go unpunished. Hicks and a

batch of his men were arrested on the following Tuesday while

helplessly intoxicated — in which state they had been ever since the

funerals — and were committed to the county jail.

Shortly after Christmas, when another man was killed, his ganger

proposed to raffle the body. The idea took immensely, and was

actually carried out. Nearly three hundred men joined in the scheme. The raffle money, sixpence a member, was to go towards a drinking

bout at the funeral, the whole expense of which was to be borne

jointly by those throwing the highest and lowest numbers. The raffle

took place, and so did the revel; but the funeral, after a

fortnight’s delay, was performed by the parish.

In the month of February, eighteen hundred and thirty-six, Frazer

took a contract to dig ballast at Tring; and, youth as I was —

although I was tall and masculine for my years — sent me down there

to have charge of the job; on which there were about fifty men

employed.

The job was bravely started, and things went on smoothly enough for

the first ten days, when, lo! it was reported that there was a bogie

in the ballast pit. These men who could defy alike death and danger

became panic stricken. The idea that the pit was haunted filled them

with a mortal terror, of which the infection heightened as it

spread. At first the current rumour was that picks, shovels, and

barrows were moved from their places nightly by the bogie; then it

came to be credited that earth was dug, barrow-runs broken up, tools

spoiled, trucks shunted, and even tipped by him in his nightly

visits. Finally, in the second week of his pranks he was said to

have appeared, and then the men struck work in a body. Reasoning

with them was useless; the old ganger, as spokesman for the rest,

declared as the result of his former experience that “there was no

tackling the old un,” and to a man they refused to re-enter the pit.

I had previously communicated with Frazer on the subject; but, in

this emergency, I despatched a messenger specially for him. He came

down the same night, bringing with him a band of chosen roughs from

Watford tunnel. These men had a ganger with an unmentionable

nickname, a fellow who declared that his chaps were prepared to work

with the devil, and for the devil, so long as they got their pay,

and to set the very devil himself to work should he appear amongst

them. Frazer expected much from this gang; and, next morning, they

commenced work in earnest. But on the second day they, too, became

possessed with the same superstitious terror as their predecessors;

and they also struck. Persuasives, promises, and threats were alike

unavailing; the men would not “go agin the bogie,” and the pit was

once again deserted.

Frazer, raved like a madman. He was under a penalty to dig so much

ballast per week, and the very urgency of his case made him

desperate. I suggested to set on a gang of farm labourers; of whom

there were plenty out of employ in the neighbourhood, and to whom

the high rate of wages would be an inducement. He assented; and, in

a day or two, we were at work again swimmingly; and continued so for

a week, when the old contagion showed itself, and another suspension

appeared inevitable. It came at last, but was for some time averted

by the allowance of rations of tommy, in addition to wages, and by

seeing that every man was half drunk before he went to work. When,

at last, these men also struck, I really think their striking was

attributable more to the intimidation practised by the old hands —

many of whom were lurking about — towards these knobsticks, than

from the influence of any other terror.

But the moral effect of this last strike upon Frazer was wondrous. Never since then have I seen a bold daring man so thoroughly beaten. He became melancholy, and told me piteously that he hadn’t got the

heart to swear. My advice was to throw up the contract; but of this

he would not hear; he would sooner cut his throat, he said. Before

doing this, however, I suggested that he ought to send for Hatley

and consult with him. He sneered at this, but eventually instructed

me to send for him. George came, heard the history of the case; and,

like a thorough general — as he has ever since proved himself —

proposed to work the pit with three shifts of men working eight

hours each during the whole twenty-four. “That,” said he, “will

settle the bogie, for he’ll never have a minute to himself for HIS

work.”

The soundness of this idea, it was impossible to gainsay. George

returned to Northchurch, and brought back to the pit sixty of his

own men. These he divided into gangs of twenty each, and kept the

pit in constant work by day and night. Every Monday the gangs

changed shifts, so that night work fell to the lot of each once in

three weeks. In this manner our bogie was laid without the

assistance of twelve clergymen, whom, Frazer had been advised by an

old lady, to engage for the purpose.

Frazer, now no longer contemplating suicide, concluded terms of

partnership with Hatley, and the new firm, resolving to launch forth

into a wider field, dispatched me to London to make tracings of the

drawings, and copy the specifications of certain brickwork to be

executed in the Hunton Bridge district. This work they obtained; the

management of the Tring ballast pit was placed jointly with the Northchurch tunnel contract under the direction of Hatley, and I was

placed upon this new work. I was a fair draughtsman,

understood the “jometry” of the thing, as the navvies called the setting out of

work; and in the truly practical character of my present labours,

found an ample recompense for the past twelve months of toil and

privation.

A publican in the neighbourhood of the bridges comprised in our

contract had given offence to the bricklayers, and they had ceased

to deal with him; but, no sooner was this bridge commenced, than he

was again favoured with their custom; although his was by no means

the nearest hostelry. Boniface, of course, was only too happy to

receive their patronage; but his self-gratulations received a check

from always finding himself short of pots and cans. He was ready to

avow that they had been sent to the men at their work; he was

equally certain they had not been returned; and it was no less true

that they were nowhere to be found. He waited a few days, and his

stock continued to decrease. The men ordered their beer in large

quantities; but, though he loved good custom and plenty of it, the

loss of pots and cans would have compelled him to decline their

further favours, if he had not been afraid of throwing the field

open to a rival. For some time he renewed his stock and bore his

loss; until at last he resolved to have the men watched as they left

their work, and, if possible, to discover who the thieves were. He

watched in vain; for, as the piers of the bridge were carried up

from the foundations, so from time to time were the publican’s cans

built in with them; and to this day they form part of the structure.

We had several north-country bricklayers at work for us, and between

two of them — natives of Wigan, I believe — while building the

parapet walls of a bridge, there arose a dispute which resulted in a

fierce battle. The question upon which issue was joined, was the

much-vexed one in the trade, of English or Flemish bond, — which was

which. To decide this, a fair rough-and-tumble fight, with some nice

purring, was proposed among their comrades, and instantly agreed to.

“Send for the purring-boots!” was the cry; and the men jumped down

from the scaffold, and repaired to the adjacent field. The

purring-boots duly came. They were stout high-lows, each shod with

an iron-plate, standing an inch or so in advance of the toe. Each

man was to wear one boot, with which he was to kick the other to the

utmost. A toss took place for right or left, and the winner of the

right having a small foot the boot was stuffed with hay to make it

fit. I refrain from particulars: I have said enough to show the

brutal nature of the affray. It lasted more than an hour. The victor

was a pitiable object for months, and his foe was crippled for life. Here I must add, that the old fashion of deciding questions by the

trial of combat prevailed widely among the first race of navvies.

More than one question of right or user so decided has remained

undisturbed to this hour. I myself saw a pitched battle, fought

between two plate-layers to decide whether “beetle” or “mawl,” was

the right name for a certain tool — a ponderous wooden hammer —

respecting which there was a difference among this body of men

throughout the district. The contest was fierce and desperate,

but eventually “mawl” vanquished; and, as a consequence, “beetle” was

expunged from the platelayers’ vocabulary.

Of course, these fights bear no proportion to, nor are they to be

confounded with those in which the combatants did violence to each

other out of personal animosity, or under the influence of drink. These disgraceful brawls were of daily occurrence, monstrous both

for their atrocity, and, in the case of navvies, for the numbers

engaged in them, and made the very name of these men a bye-word and

a terror. For navvies, it must be borne in mind, do not usually

fight single-handed, or man to man; their system of fighting is in

whole gangs or “all of a ruck,” as they term it. So,

newspaper-readers may remember that, “desperate affray with

navigators,” or “fearful battle between navigators and the police,”

or whoever it may be, generally used to head the accounts given of

disturbances in which those men were engaged; but an account of a

fight between two of them was very rarely seen.

At length, in the summer of the year eighteen hundred and

thirty-six, the fearful depravity of the men working upon railways,

and the demoralising influence upon the surrounding population,

became matter of public notoriety (I speak of the district within my

own observation); and missions were organised by various religious

sections of the community for their reclamation. The object was most

praiseworthy; for by no class was reformation more radically

required than by railway makers of every grade, from the gaffers to

the tip-boy. In my humble opinion, however, the efforts made were

rather calculated to bring the object attempted into disrepute, than

to accomplish it; and that these efforts failed is not to be gainsayed. Thus, many well-dressed, and doubtless well-meaning

persons, obtained permission to visit the men on the works, during

meal times, with the view of imparting religious instruction to

them, and did so. The distribution of religious tracts, and the

usual machinery of proselytism, were shortly in active operation,

and the men’s dinner-hour, instead of being a period of rest and

relaxation, was converted into a time for admonition and harangue.

An elderly man who was very officious in the distribution of tracts

— which would not be received — all at once found them acceptable

and even in demand. He was overjoyed, talked among his fellows of a

revival, and came loaded daily with his wares. The success of his

labours was now spoken of as a decided and encouraging fact, and

doubtless would have been considered so till now, had he not one day

been taken to a shanty, the walls of which had been doubly papered

with his tracts, over which a thick coat of whitewash was then being

plastered. On one occasion I remember walking down to the tunnel,

and was joined at Hazlewood Bridge by a missionary. He detailed to

me how he had nearly been a martyr to the cause; how he had been

twice nearly drawn half-way up the shaft in a bucket and suddenly

let down; how he had been run out on trucks to the tip-head; how he

had been shunted on a lorry and left upon the spoil-bank for hours;

and how all sorts of practical jokes had been played upon him, and

yet he felt the interest of the men so deeply at heart that, despite

all, he must persevere. I could respect and admire this enthusiast;

although I did not think he used the right means to attain his

purpose.

The right steps towards the conversion of navvies were soon

afterwards taken by Mr. now Sir T. M. Peto, Mr.Thomas Jackson, Mr.

Brassey, and other gentlemen; who, having entered into contracts on

a vast scale, made the social condition of their men a matter of

primary consideration. In several districts suitable dwellings were

erected for them; in towns, cottages were run up. For these a small

rent was deducted from wages; but, in some cases, suitable lodgings

were provided and paid for by the contractor. The gaffers and

gangers were not allowed to keep tommy and beershops; wages were

paid in money, and there was no truck. The hours of labour also were

duly regulated; and regulations as to the proper conduct of work in

hand and those executing it were duly enforced. Beer in barrels,

casks, and even in pails, had formerly been brought upon the works. All this was strictly forbidden; men were no longer brought fuddled

to their work, nor kept fuddled at it, in order that, under the

influence of drink, they might get through more in a given time. A

certain quantity of beer was permitted to be brought to each man

during the hours of labour; this being regulated according to

circumstances and the nature of the work. Under such rule as this,

railway-makers of every trade — and the navvie more especially —

became at length somewhat disciplined. Self-respect was inculcated;

respect for the laws of sobriety, and decorum followed in due

course; and thus was effected the great moral revolution in the

condition of the railway-labourer, to which all who have been

conversant with railway operations during the last twenty years, can

most emphatically testify.

――――♦―――― |

|

RAILWAY REFRESHMENT ROOMS

“IT NEVER YET

REFRESHED A MORTAL BEING.”

|

|

|

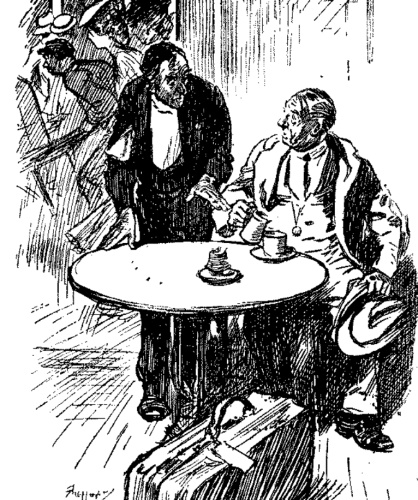

Scene—Railway Refreshment Room.

Thermometer 90°

in the Shade. Waiter (to traveller taking tea).

“Beg pardon, sir, I shouldn't

recommend that milk, sir;

leastways not for drinking purposes.”

Punch Magazine. |

Thus spoke Charles Dickens, referring to one such refreshment room ―

believed to have been that at Rugby ― in his series of tales based

on the mythical (or was it?) Mugby Junction.

It must be said that

railway catering down the years has not met with universal

approbation. One of its earliest critics was none less than

Isambard Kingdom Brunel, who, in 1845, with regard to the

coffee served at Swindon’s refreshment room, had this to say to its franchisee:

|

“I assure you that Mr. Player was wrong in supposing that I

thought you purchased inferior coffee. I thought I said to him that

I was surprised you should buy such poor roasted corn. I did not

believe you had such a thing as coffee in the place; I am certain I

never tasted any. I have long ceased to make complaints at Swindon. I avoid taking anything there if I can help it.” |

Charles Dickens felt so strongly about poor quality railway catering he used

his

experiences as the basis for his tale The Boy at Mugby, later referring to it in

his periodical (All The Year Round) in these terms . . . .

“. . . . a tyranny under which the British railway-traveller has

groaned ever since railways were. It was to the extirpation of the

evils arising from this tyranny that ‘Mugby Junction’ was especially

dedicated; and it seems appropriate that the readers of this journal

should be introduced to the doughty champions who have grappled with

and conquered the peculiar abuses we have so long inveighed against

in vain. The pork and veal pies, with their bumps of delusive

promise, and their little cubes of gristle and bad fat, the scalding

infusion satirically called tea, the stale bad buns, with their

veneering of furniture polish, the sawdusty sandwiches, so

frequently and so energetically condemned, and, more than all, the

icy stare from the counter, the insolent ignoring of every

customer’s existence, which drives the hungry frantic . . . . ”

From All The Year Round, Charles Dickens, 28th

December 1867

On the subject of

“sawdusty” railway sandwiches, the novelist Anthony

Trollope felt “the real disgrace of England is the

railway sandwich ― that withered sepulchre, fair enough outside, but

so meagre, poor and spiritless within.” As for travellers on the

London and Birmingham Railway:

|

|

|

Charles Dickens in the

refreshment room

at Mugby Junction (Rugby). |

“At the Wolverton station, fifty miles distant from the

metropolis, a stay of ten minutes is allowed for refreshment . . . .

the respective carriages suddenly disgorge a motley and

miscellaneous group of bipeds, who rush to the salon à manger, and

commence the work of demolition on all things substantial and

condimental there displayed. Appetites appear to be at high steam

pressure, and to work with most annihilating power. Extensive as is

the refectory, it is usually crammed, to the impossibility of one

half the number of persons getting within reach of the abundant fare

provided . . . . But time is up, and the crowd resume their seats,

the engine again concentrates its vaporous power, and away fly the

million on their destined way.”

From Bentley's Miscellany, Volume 20, 1846

“A word also for the Birmingham folks. At the station there is

accommodation provided for the Grand Junction passengers ― apart

from the Birmingham ones. The room will seat about one half of the

requisite number, and consequently at dinner as many are standing as

silting to take their meal, and a slovenly business it was on the

occasion when I was present ― worse than the accommodations at the

average of inns on any of the great lines of road either in England,

Scotland or Wales. In fact, all smells of monopoly. Try the

Wolverton station, half way to Birmingham, after a ride of three

hours, and you will find hot elder wine, Banbury cakes, and bad ale

― if you can get it, for the crowd! What a paltry and childish

accommodation for travellers under, what is admitted to be an

improved system of transit. Who established the refectory at

Wolverton, and into whose pockets do the profits find their way?“

Letter to the Editor of the Railway Times,

18th May 1839

“We have sometimes

seen in a pastrycook’s window, an announcement

of ‘Soups hot till eleven at night,’ and we have thought how very

hot the said soups must be at ten in the morning; but we defy any

soup to be so red hot, so scorchingly and intensely scarifying to

the roof of the mouth as the soup you are allowed just three minutes

to swallow it the Wolverton Station of the London and Birmingham

Railway. Punch, in the course of his peregrinations, a day or two

ago, had occasion to travel on this line and was invited to descend

from his carriage to refresh at the Wolverton Station. A smiling

gentleman, with an enormous ladle, insinuatingly suggested, ‘Soup

Sir!’ when Punch, with his usual courteous affability, replied,

‘Thank you;’ and the gigantic ladle was plunged into a cauldron

which hissed with hot fury at the intrusion of the ladle.

We were put in possession of a plate, full of a coloured liquid that

actually took the skin off our face by its mere steam. Having paid

for the soup, we were just about to put a spoonful to our lips, when

a bell was rung, and the gentleman who had suggested the soup,

ladled out the soup, and got the money for the soup, blandly

remarked, ‘The train is just off, Sir.’ We made a desperate thrust

of a spoonful into our mouth, but the skin peeled off our lips,

tongue, and palate, like the coat a hot potato. We were compelled to

resign our soup, probably to be served out to the passengers by the

next arrival.

This is no idle tale, but a sad reality; and the great moral of the

tale is, that the soup-vender smiled pleasantly, and evidently

enjoyed the fun, which, as a pantomime joke, is not a bad one.“

From Punch, Volume 9, 1845

Eliezer Edwards, on his way to Birmingham on business, was impressed

by the facility provided at the earliest of Wolverton’s stations,

although perhaps not by the crowd:

“On Sunday, the 14th of July, in the year 1839, I left Euston

Square by the night mail train. I had taken a ticket for Coventry,

where I intended to commence a business journey of a month’s

duration. It was a hot and sultry night, and I was very glad when we

arrived at Wolverton, where we had to wait ten minutes while the

engine was changed. An enterprising person who owned a small plot of

land adjoining the station, had erected thereon a small wooden hut,

where, in winter time, he dispensed to shivering passengers hot

elderberry wine and slips of toast, and in summer, tea, coffee, and

genuine old-fashioned fermented ginger-beer. It was the only

‘refreshment room’ upon the line, and people used to crowd his

little shanty, clamouring loudly for supplies. He soon became the

most popular man between London and Birmingham.”

Recollections of Birmingham,

Eliezer Edwards (1877)

A couple of years later, an American traveller called at the second

of Wolverton’s refreshment rooms:

“. . . . the train, that had stopped at two or three stations

before, came to a halt with a great scream; and policemen, banging

open the doors, told us this was Wolverton station, and that we

might have ten minutes for tea and refreshment. It was about

half-past eleven at night; and remembering that it was a good time

for supper . . . . I descended and entered the refreshment room, a

long strip of building, with a long table in the midst covered with

all the delicacies of the season, to be had at moderate prices. The

table is served by at least forty of your enchanting sex; and,

accordingly, from one of them, who giggled very much when I asked

for a gin-sling, and told me they kept no such thing, I was fain to

accept a glass of sherry, a couple of Banbury cakes . . . . and a

large lump of pork pie. So provided, I jumped lightly into my seat

again . . . . and in a few moments we were in motion again; and I

sunk back to think of America, ― and to sleep.”

From Fraser's Magazine, Volume 24, September

1841

And so to Wolverton’s refreshment rooms as seen through the eyes of

Sir Francis Bond Head, onetime soldier, adventurer, unsuccessful

Lieutenant Governor of Canada, none too successful Chairman of the Grand Junction

Canal Company, and a writer on many subjects. Having described

Wolverton works, Head then moves on to address the Station’s

catering facilities:

“The magnitude of the establishment

[the Works] will best speak for itself;

but as our readers, like ourselves, are no doubt tired almost to

death of the clanking of anvils ― of the whizzing of machinery ― of

the disagreeable noises created by the cutting, shaving, turning,

and planing of iron ― of the suffocating fumes in the brass-foundry,

in the smelting-houses, in the gas-works ― and lastly of the

stunning blows of the great steam hammer ― we beg leave to offer

them a cup of black tea at the Company’s public refreshment-room, in

order that, while they are blowing, sipping, and enjoying the

beverage, we may briefly explain to them the nature of this

beautiful little oasis in the desert.

In dealing with the British nation, it is an axiom among those who

have most deeply studied our noble character, that to keep John Bull

in beaming good-humour it is absolutely necessary to keep him always

quite full. The operation is very delicately called ‘refreshing

him;’ and the London and North Western Railway Company having,

as in duty bound, made due arrangements for affording him, once in

about every two hours, this support, their arrangements not only

constitute a curious feature in the history of railway management,

but the dramatis personæ we are about to introduce form, we

think, rather a strange contrast to the bare arms, muscular frames,

heated brows, and begrimed faces of the sturdy workmen we have just

left.

The refreshment establishment at Wolverton is composed of ―

1. A matron or generallissima.

2. Seven very young ladies to wait upon the passengers.

3. Four men and three boys ditto.