|

THREE

TRING

INDUSTRIES:

Canvas Weaving, Brickmaking, Metalworking

Brick makers

Wendy Austin

――――♦――――

CONTENTS

――――♦――――

FOREWORD

In the Victorian period, most towns, and even villages, were

self-sufficient in that local businesses and shops provided for

nearly all of the inhabitants’ day-to-day needs. Tring was no

exception, and nobody had to travel far to find both employment and

commodities.

Apart from the activities at Tring silk mill, which was an unusually

large concern to find in a small market town, various other

industries sprang up, some of course related to transport

necessities in the age of the horse. These small businesses

were founded and run by craftsmen, and often passed down through the

generations, although some of the stories ended sadly due to

bankruptcy or forced closure.

The subject of the silk trade in the town has been covered in a

separate book,

Tring Silk Mill (published 2008,

reprinted 2014). The essential industry of flour milling has

also been written up in

Gone with the Wind: Windmills and those around

Tring (published 2010). This present booklet covers

three other industries trading from the late 18th century and, to a

certain extent, to the present day. Canvas weaving has now

disappeared completely from the local scene but ironworking, forging

and one firm of brickmakers still carry on in the locality.

It has been difficult to establish the exact dates and persons

involved in some of the old industrial concerns, especially

brickmaking. But the content is as accurate as can be

discovered at the time of writing; if any reader knows more details

of these professions in Tring, I should be pleased to know.

References to source material are acknowledged in the main text or

footnotes, but my thanks for information and loan of pictures also

goes to Michael Bass, Shirley Bloomfield, Harvey Burch, Jill Fowler,

Julie and Gilbert Grace, staff of Hammer & Tongs, Jimmy Honour, John

Horn, Bert Hosier, Mick Jones of BBONT, the late Ron Kitchener, Jon

and Debbie Lovelace, staff of Matthews Brickworks, Rebecca

McCloskey, David Metcalfe, Stuart Pearce, Ann Reed, David Ridgwell,

Paddy Thomas, Elizabeth Tory, and especially to Ian Petticrew who

has formatted and edited this book.

W.M.A.

December 2017

――――♦――――

1. EARLY INDUSTRY IN TRING

From the time of its first Market Charter in 1315 and before, Tring

has always been a small agricultural market town, but in the 19th

century some successful industry was established, helped in measure

by the coming of the

Grand Junction Canal and later, to

a greater extent, by the

London & Birmingham Railway.

In 1823 a successful cotton and silk manufacturer, William Kay

(1777-1838), purchased the Tring Park estate but not with the

objective of living in the mansion house, for he preferred to remain

in London minding his other investments. He claimed to have

spent £30,000 erecting and equipping a five-storey silk throwing [1]

mill in Brook Street which processed imported skeins from China and

Bengal ready for despatch to various silk weaving mills, both

locally and in Macclesfield and Coventry. This undertaking was

powered by a huge 22ft.-diameter waterwheel driven by the diversion

of various streams which ran underground beneath Tring; later this

was supplemented by steam.

At its peak the mill employed as many as 600 people, including a

large number of children (some as young as eight years old) sent

from both local workhouses and those in St Margaret’s and St

George’s parishes in London. The children were housed in a

long dormitory building fronting the mill, provided with work

clothes, and reasonably well fed. All hands worked very long

hours, although the children were supposed to receive some

rudimentary education, and conditions may not have been so harsh for

them as those in mills in the north of the country.

In 1872 the first Lord Rothschild (1840-1915) acquired the Tring

Park estate of which the mill was part; by then, the silk trade

generally was already in serious decline due mainly to cheaper

foreign imports. Not wishing to cause hardship, he continued

to let the business run at a loss until the doors were finally

closed in 1898. The top two storeys and tall chimney were then

removed, but the remainder of the original premises – somewhat

altered – can still be seen in Brook Street and now serve to house a

variety of industrial units.

Very much smaller concerns were the canvas weaving shops which

sprang up in various parts of the town; looms were also set up in

the Parish workhouse. These workshops produced all types of

canvas from that used on embroidery frames to coarse quality for

horses’ nosebags. The largest premises were in Park Road, and

others were established in Akeman Street,

Dunsley,

off Langdon Street, and later, Charles Street, the latter not

closing until the 1920s. Again, some local child labour was

used, usually boys referred to as ‘half-timers’, meaning they

attended school for part of the day either before or after working

in the factory.

From the medieval period onwards various types of metalworking was

carried on in Tring. When all transport was horse-drawn, local

smithies were a necessity, and as agriculture became more

mechanised, blacksmiths could be found in even the smallest towns.

Some businesses combined forges at the rear of a shop which sold all

sorts of hardware, some made on the premises. Examples of work

produced by these firms can still be seen around Tring.

One industry in the town that still operates today is milling –

Heygates at

New Mill being the last working flour mill in Dacorum.

At Gamnel a windmill had been built on a strategic site alongside

the canal, joined later by a brick-built six-storey mill erected

under the ownership of the Mead family at the time when steam was

replacing wind power (the windmill finally being demolished in

1911). The adjacent wharf was then a busy place as the trade

included dealing in hay, straw, gravel, coal, coke and general

carrying by water. Part of the complex included a

boat-building business run and later owned by the Bushell Brothers,

a concern that Thomas Mead had established to maintain his own fleet

of narrow boats. Part of the original mill building remains,

but its interior has long been transformed. The mechanical

shafts, cogs, belts and sets of grindstones it once housed have been

replaced by pipe-work that connects the grain silos with rows of

cabinets housing the computer controlled steel milling rollers.

Over the years many other small industrial concerns served local

needs, including several breweries, a tannery, a carriage builder, a

lime works, and a mineral water factory. Brief mention should

also be made of the two cottage industries of Tring, straw plaiting

and, to a lesser degree, lace making. Essential to the local

economy in the 19th century, this work could be carried out at home,

mainly by women but also by children. Without it many would

have gone hungry for it helped to keep the wolf from the door,

especially during times of agricultural depression when there was

little employment for the menfolk.

However, just over one hundred years ago a report in The Bucks

Herald lamented:

“. . . . by late Berkhamsted has become predominant. Tring

formerly was as an important town as Watford then was and, perhaps

excepting Hemel Hempstead, its market was the largest in West

Hertfordshire. With a flourishing silk mill, employing a large

number of people, several canvas-weaving works doing good business,

and the plait industry in and all around the district, Tring was a

thriving place and a large measure of enterprise and endeavour

obtained. But during the last generation all these industries

have almost died out and the population declined in all the villages

around Tring. Tring has necessarily had to take a backward

place by reason of its insular

position and its distance from the railway . . . . ”

Sic transit gloria

CHAPTER

NOTES

1.

Silk throwing is the industrial process wherein silk that has been

reeled into skeins, is cleaned, receives a twist and is wound onto

bobbins. The yarn is now twisted together with threads, in a

process known as doubling. Colloquially silk throwing can be

used to refer to the whole process: reeling, throwing and doubling.

Silk had to be thrown to make it strong enough to be used as the

warp in a loom.

――――♦――――

2.

CANVAS WEAVING

Canvas, a durable plain-woven cloth, was traditionally made from

hemp (cannabis sativa) an undemanding plant with a long fibrous stem

and six times as strong as cotton. The fibres, from 3ft. to

15ft. in length, commonly called bast, grow on the outside of the

woody interior of the plant’s stalk, and under the outermost part of

the bark.

Stem of the hemp plant

(Cannabis Sativa)

There does not appear to be a tradition of hemp growing in the Tring

area (although there is a local ‘Hemp Lane’ which winds up from the

main road to Wigginton village), and no one can say exactly why

canvas weaving started as a small industry in various locations in

the town.

Tring local historian Arthur Macdonald writing in the 1890s states:

“The canvas industry is said to have been introduced [to

Tring] by a colony of Flemings who settled here. Some of

their names remain, as Delderfield or Delderfeldt (‘Darofel’), and

Wilkins (‘Wilquin’)”. These people who migrated to England

following persecution of their Calvinist faith on the Continent

brought with them many craft skills, and were often master weavers

or journeymen specializing in various branches of the textile

industry, mainly silk, although some Huguenots had practiced the

craft of canvas sail making in England since long before then.

No firm records can be discovered of these descendants of exiles

actually arriving in Tring, but certainly a number were connected

with Hemel Hempstead, where the Fourdrinier brothers installed a

French-designed machine for the paper-making industry in that

locality and where, it is said, the colony had its own cemetery. [1]

The first documented evidence of canvas weaving in Tring comes from

entries in the Militia Lists [2]

from the middle to the end of the 18th century, and these record men

working as rope-makers, as well as one flax man and one hemp

dresser. [3]

By 1772, names of members of Tring families engaged in canvas

weaving appear, including one Cutler, two Catos and several Olneys.

Mention is made in a legal document of 1815 relating to lands held

by the Tring Park Estate where the name Jackson Harding and several

other weavers are shown as well as a ‘weaving shop’, and it is

possible that this refers to a premises engaged in canvas weaving.

(One of the Olneys – see below –had the given name of ‘Harding’,

implying descent or connection with Jackson Harding.)

Pigot’s Directory from 1825 to 1839 lists four proprietors of

weaving shops, and Arthur Macdonald describes these as follows:

“Entering the town from the east, the first building on the left

is the pretty pair of cottages [Dunsley Cottages] built by

Lord Rothschild on the site of an old canvas weaving shop, then

owned and occupied by Mr John Burgess, and before him by Daniel and

Harding Olney. The Olneys were a family of some position in

the town, being the principal canvas manufacturers and possessing

several properties. William Olney had weaving shops in Akeman

St., which he converted into the Akeman Brewery. [4]

The present brewery in Frogmore St. was first a canvas factory

worked by one Cutler. William Cato commenced canvas making at

The Oak in Akeman Street, and subsequently built the factory in Park

Road which is now the only relic of the trade.”

|

|

|

Thomas

Olney (b. 1790) |

By ‘some position

in the town’ Arthur Macdonald presumably refers to the Olney

family’s high standing at the New Mill Baptist chapel, at a time

when Non-Conformity was at its height. Daniel Olney senior was

Deacon at that church, and his brother, Thomas, who had been sent by

their father to London to trade as a wholesale mercer went on to

become one of the Reverend Spurgeon’s [5]

right-hand men.

All qualities of canvas were woven in the various workshops, from

heavy-duty for sacking, lighter weight for work smocks, down to very

fine products for use on embroidery frames and for curtain lining.

The smock shown below is worn by Tring labourer James Stevens, these

garments being the traditional wear of men and boys engaged in farm

work, and often embroidered with emblems showing their particular

trade, thus enabling them to be readily identified at the annual

hiring fairs. [6]

John Burgess, advertising his trade as “canvas manufacturer of

open canvas for ladies needlework, gunpowder canvas, cheese cloths

etc.” carried on weaving in the premises at Dunsley until it was

shut down in 1883 [7]

and demolished some years later, along with other nearby properties,

to make way for the erection of Dunsley Cottages opposite the Robin

Hood pub.

The following extract of 1840 taken from Osborne’s Guide to the

London & Birmingham Railway, gives some description of the

procedures at the largest of the canvas workshops operating at that

date:

“Tring claims to have commenced the canvas trade before any other

town in England. There are four manufactories, in which

upwards of a hundred persons are employed. The yarn is brought

from Yorkshire, and wove by hand-looms; the first process is

performed by boys; it consists in winding the yarn from the hand

upon the spools, these are then taken to the warping mill to be

wound into large warps ready for the loom; it is then taken to the

loom and woven by men. The work is not considered very hard

and the time of daily labour is from ten to twelve hours; the men

get about 16s. per week, the boys about 3s. Mr Cutler, the

largest manufacturer in the town, works 20 looms and employs 40

persons.”

|

|

|

James

Stevens (1808-1911) |

In addition to

his canvas weaving business, George Cutler also bought a small silk

throwing mill in Frogmore Street, Tring, a venture that had not

flourished under the previous ownership of William Shipley, when a

notice of ‘Sale under Distress of Rent’ appeared in the Bucks

Herald in 1858. Three years later Cutler also shut up shop

and sold the premises and all assets.

As mentioned by Arthur Macdonald, William Cato moved his weaving

shop from Akeman Street to Park Road, where Thomas Cato is listed in

the 1851 census as employing 11 men, and in Kelly’s Directory

of 1869 as “manufacturer of open canvas for Berlin work, [i.e.

large-stitch wool embroidery], and gunpowder canvas.”

The census returns for Tring show all those engaged in the canvas

weaving trade, including the ‘quill winders’ who were lads known as

‘half-timers’, since they were obliged to attend school for a half a

day in either the morning or afternoon. The rate then was

half-a-crown for half a day which was not considered a good wage,

resulting in a constant change of boy workers. The following

photographs show the Park Road weaving shop as it was around the

turn of the century.

Cato’s weaving shop in Park Road, exterior and

interior.

It appears that the men from the workshops were reasonably good at

cricket, as an account of 12th August 1871 in the Bucks Herald

informs that a match played on the Bowling Green [8]

between Tring United Club and the Canvas Weavers resulted in a win

for the latter.

Most towns of any size had at least one rope maker, and listings for

Tring in a trade directory of 1839 show four Rope and Twine Makers,

all working in Market Street (now called the High Street). In

1851 John King, described as a Master Rope Maker, is plying his

craft of rope and twine spinning in his premises in Park Road where

he remained until approximately the early 1890s. It was

perhaps no coincidence that his house and workshop were almost

immediately opposite to Cato’s canvas weaving shop, as both trades

would have required similar materials.

The latter was taken over by George Cato, but at the time of his

death in 1906 the business was in sad decline. Thirty years

before this, in reports of political meetings in the town, the

Conservative Party had bemoaned the fact that the number of Tring

workers in both the silk and canvas factories had dramatically

reduced: “Not many years ago there used to be something like 60

canvas weavers in the town, and now there were 16. Would they

know the reason? It was Free Trade. The Frenchman made

the canvas and it was admitted here duty free, so that the

Englishman could not compete with him.” This laid the

blame firmly on French imports endorsed by the Free Trade policies

advocated by the Liberal Party.

George Cato’s obituary in the Bucks Herald in 1906 outlined

other causes and also lamented that

“. . . . in recent years [the industry] has fallen upon

evil times, the old method of weaving having been superseded by more

rapid and economical processes. The old weaving shop in Park

Road has played its part in the industrial history of Tring, and

there are men employed there now who have spent the whole of their

working life – in some cases more than 40 years – in the shop.

To them and to others the future of the business is a matter of

grave anxiety.”

It may be that a few of them found employment in the fifth and last

canvas weaving premises to be operational in Tring. Named

Gravelly Furlong, sited at the rear of No.12 Charles Street, it is

shown in Kelly’s Directory of 1855, and was also owned by a

Cato (James), and later taken over by Charles Cato. He

produced beautifully fine, soft canvas especially used for the

lining of curtains, the merit of which was recognised in 1886 at a

large Industrial Exhibition held in Berkhamsted when Charles Cato

was awarded a medal. Hearsay, although this cannot be

verified, states that the shop also wove high quality cloth for army

uniforms. Several prestigious department stores were

customers.

In February 1907, when the workforce went for dinner, a disastrous

fire broke out in the drying room near to a stove; a length of

canvas, part of a large order for Whiteleys of London, ignited.

Cato attempted to put out the blaze but within a few minutes the

building was enveloped in flames. Fortunately the Fire Brigade

prevented the fire spreading to adjacent houses, but they were

unable to save the workshops. The damage was estimated at

around £800 but this was covered by insurance, and five months later

plans for a new weaving shop had been passed by the Council and a

rebuild was soon underway. After the death of Charles Cato,

the business was carried on by his son who had spent his working

life with his father until ill health eventually forced his

retirement.

This last remnant of the industry eventually went the way of the

others, when it finally closed down following the death of Frederick

Cato shortly before WWII. The premises then became a ladies’

clothing factory, specialising mainly in sewing coats. Known

as B. H. Baker & Son and owned by Barnet and Annie Baker, the firm

employed both males and females, and in the 1950s frequent

advertisements appeared in the Bucks Herald offering “the

opportunities for young people to learn a useful trade in tailoring,

machining, finishing and pressing.”

Arthur Baker conveyed the property to Kenneth Pegg [9]

in 1977 and an application was submitted for change of use from

industrial premises to conversion to two private dwellings.

Pegg extensively remodelled the building, using various interesting

items of architectural salvage. Now approached by a drive

leading off the upper part of Albert Street, and after several

changes of ownership, the property has been converted to form one

large house.

Chapter Notes

1. From article in The Gazette, 12 May 2007.

2. From 1757, lists of men from various parishes with liability to

serve in the military if called upon. Their ages, occupations

and any disabilities were shown.

3. A worker who separated the coarse part of the hemp with a toothed

instrument called a hackle. Once smooth, the hemp could be

spun.

4. From Bucks Herald 12 February 1859: For Sale by Mr. W.

Brown by directions from the Trustees of the late Miss Sarah Olney “A

Brewery and a Canvas Weaving Shop of six floors, drying house,

stabling and other convenient buildings ……….”

5. One of the leading Non-Conformist churchmen of the era.

6. Hiring fairs, also called statute or mop fairs, were regular

events in pre-modern Great Britain and Ireland where labourers were

hired for fixed terms.

7. Account from the Bucks Herald.

8. An area of meadow behind Brown’s Maltings in Akeman Street.

9. Kenneth Pegg was convicted, tried and sentenced to a 26-year term

for murder in 1985.

――――♦――――

3. BRICKMAKING IN THE CHILTERNS

Overview

The first stage in brickmaking is to obtain a supply of suitable

clay. That used for brickmaking required several properties;

it had to be plastic when mixed with water, have enough tensile

strength to keep its shape, and its particles must fuse together.

The deposits of brickmaking clay around Tring were insufficient to

support large commercial businesses, but sufficient to enable local

brickyards to manufacture on a small scale. These brickyards

also provided welcome employment in a largely agricultural area

where work at times was spasmodic due to weather conditions and the

slumps in agriculture caused by cheap imported foodstuffs, such as

American and Canadian grain and, later, frozen meat.

Clay was traditionally dug in the winter months to allow it to be

broken down by frost. It was then wetted and mixed with a

loam-like substance such as sawdust or wood chippings. An

account by Bert Hosier, born 1928, [1] gives a

good description of the site at Outwood Kiln, Aldbury, (Chapter

4) during the

time of his childhood. With his permission, an extract is set

out below:

“. . . . I well remember the brickyard in full working order, the

deep clay pits where all winter the men toiled digging out the clay,

filling the large round wooden buckets which were hauled up by hand

windlass. One man had a slight hump on his shoulder, and I

used to wonder if he had been hit by a bucket. A light railway

track with side-tipping trucks took the clay to the working area,

the only braking system being a length of cordwood forced against

the iron wheels. Gradually a large mound of clay rose up near

the brickmaking shed, ready for better weather to arrive.

In due course the clay was ‘soaked down’, i.e. pulled from the mound

with long handled hoe-like implements, then well watered and tipped

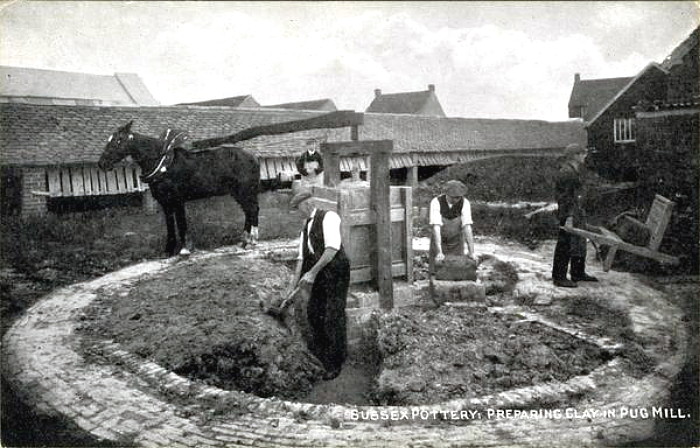

into the pugmill. [2] This was a

hole in the ground housing grinding blades turned by the constant

perambulations of a horse attached to a wooden arm. The pug

was barrowed to the making tables where four men actually made the

bricks, slapping an accurately guessed amount of clay into the

sanded iron mould, any surplus being taken off with a wooden

striker. The fresh bricks were turned out and placed on to the

special iron-wheeled flat barrow to be wheeled out to the ‘hacks’

(i.e. frames for drying bricks before firing) and they would then

dry in the sun.

Stacked in an openwork formation and with hack covers always at hand

in case of rain or frost, they remained in the open until ready for

burning. During this time they would be ‘skintled’ (i.e.

turned) to present a new face to the sun and air. When safe to

handle, the bricks were stacked in the open topped kilns where

firing and temperatures, learned by experience over many years,

turned the clay into the multi-coloured reds and greys of the facing

bricks for which the yard was renowned.

The

grade of clay needed eventually ran out, so the fence would ‘fall

down’ and be replaced a few yards back to gain more ground and clay.”

Another child resident of Outwood Kiln cottages was Mary Janes

(d.1978) whose father was one of five brick-makers working at the

site. She has left a few recorded memories of how things

were then:

“. . . . The bricks were made in wooden moulds, the base of which

was screwed to the table and the sides came off. These moulds

were dusted with sawdust, the clay was beaten in hard, the excess

scraped off, and the bricks were laid in long barrows to be stacked

and dried in the sun. There was no piped water, the supply

coming from a tapped spring feeding the horse pond at the back of

the cottages. It was a very busy yard which turned out facing

bricks of best greys, multis and reds (which had not been baked hard

enough).”

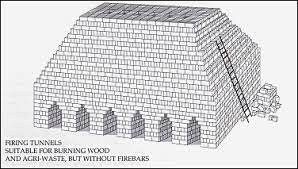

Above: clamp Below:

Scotch kiln

When dry

the bricks were then fired, for which the use of ‘clamps’ was the

oldest and most rudimentary method. In its basic form a clamp

is a carefully constructed stack of unfired (or ‘green’) bricks,

such as that pictured above. However, most brickyards used

some form of permanent kiln, such as the ‘Scotch kiln’. This

was a clamp enclosed within four permanent walls with fire holes in

the sides that led under a perforated floor onto which the bricks

were carefully stacked.

Firewood and coal were the most common fuel sources used for firing

bricks. The heat from the fire passed up through the bricks

and out of the top of the kiln. Smaller brickyards generally

had single fire kilns into which the bricks were loaded, the kiln

lit, and the bricks burnt. The kiln had then to be allowed to

cool before the bricks could be removed, the process taking about a

week to complete.

In addition to using local clay, Tring brick-makers also obtained

supplies of clay and sand from other areas, from which they moulded

the ‘multi-coloured’ bricks featured in some of their

advertisements. Basically, iron chemicals produce red clay;

magnesium produces cream; and carbon produces various shades of

grey, blue and black. As with pottery making, glazed bricks

are obtained by adding salt to the kiln.

As with other labouring occupations of those times, the work of the

brickmaker was hard and the hours long. Until 1871 child

labour was used extensively in large brickworks, and census returns

show that boys were employed in some of the brickyards in the Tring

area. [3]

Other uses of local clay and flint

The flints-with-clay found in the area of the Chiltern Hills around

the Hertfordshire/Buckinghamshire border yielded much valuable

material that could be put to a number of uses. Old maps of

the Victorian period are dotted with pits of different types, marked

as clay, chalk or gravel.

A practice known as ‘clay clapping’ (aka ‘puddling’) was carried out

in some local hilltop villages such as Cholesbury and Buckland,

whereby clay was dug and then used to line ponds, ensuring retention

of water for both agricultural and domestic use in times of summer

drought. Considerable amounts were also used to line the beds

of the newly-built canals; it was laid in slabs, and then impacted

by driving herds of cattle along each stretch.

Before the age when tar mixed with iron slag (a by-product of the

steel and iron industries) was used, roads were repaired with

flints. These were picked off farmers’ fields, often by

children who were paid small amounts for what they gathered.

The flints would then be split by a ‘flintknapper’. Both

knapped (i.e. split) and unknapped flints were also used as

building material in conjunction with bricks or stone, and many

examples can be seen of what became a vernacular style in towns and

villages all over the Chiltern Hills (e.g. Tring Parish

Church).

The local builders of the time well understood the qualities of the

bricks and limes that were burnt at the kilns in the area. For

mortar they used the scrapings from the flint-surfaced roads and the

trimming of the verges; these they called ‘sidings’. During

the winter months the roads were scraped and their verges cut and

the material so obtained was placed in heaps on the grass borders to

be sold by the mile by the local authority.

Flintknapping

– Charles Delderfield of Aldbury breaking flints for roadstone

Tring Parish Church

- knapped flint and stone construction

Chapter notes

1. A Hedgehog’s Guide to Northchurch, Bert Hosier, pub.1994.

2. A machine in which clay and water are mixed, blended, or kneaded

into a desired consistency.

3. Charles Smith (1831-1895), a child brickfield worker in the 1840s

who later became a philanthropist and campaigned tirelessly for the

reform of this practice. Eventual success came with the

amendment to the Factories and Workshops Act of 1871 that banned the

employment of boys under ten and girls under sixteen from working in

the production of bricks and tiles.

――――♦――――

4. BRICKMAKING – OUTWOOD KILN, ALDBURY

On the Dairy Farm area of the Ashridge estate before the end of the

16th century, two acres of land known as Lyons Grove were sold and

cleared in preparation for the erection of a brick kiln, but by

about 1723 this brickyard had ceased to function. However,

brickmaking was still carried on in the immediate area, for when one

Daniel Puddefoot, tenant of the farm, died in 1744 his inventory

included “…. For bricks and clay and sand and barrows and all as

belongs to the Brick Trade - £3” (Herts Record Office, 105 HW

12).

Once the 7th Earl of Bridgewater inherited the Ashridge estate in

1803, great changes were in force. An enlightened and

forward-thinking landlord, the Earl brought many improvements to his

properties and land, including plans for a brickworks approached by

a section of new road leading from Tom’s Hill to Northchurch Common.

Known as Outwood Kiln, this enclosure comprised three buildings

forming part of the brickworks, plus a plot containing two cottages

alongside occupied by 1838 by John Howard and Thomas Cox.

Brickyard at Outwood Kiln,

c.1930s

The exact date when the brickworks became operational can be

reasonably estimated since it was not included on the Ashridge map

of 1821, but cottages described as “at the Brick Kiln on the

common” were being rated by the Vestry four years later.

There appeared to be no protests to the necessary enclosure of five

and a half acres of common land; nor an objection by members of the

Vestry, in fact no recorded disapproving comment of any kind.

It seems likely that it was made clear from the outset that the kiln

would provide work, and that it would produce bricks to build better

homes for the tenants of the estate.

The source of clay for Outwood Kiln would have been the same as, or

similar to, that used by the brick and tile makers at Lyons Kiln as

mentioned above. The bricks, old or new, were a soft pinkish

red in colour and can still be seen in many buildings in Aldbury.

Preparation of clay (‘pugging’) for brick making probably changed

little between the opening of Outwood Kiln and the end of the 19th

century when a horse-gear was in use. The animal walked round

and round, pulling and so turning a horizontal wheel to which was

geared the paddle used to stir the clay.

A horse powered pugmill

Clay and chalk, for producing lime, could have been fired together,

as Jean Davis in her Aldbury the Open Village (pub.1987)

gives a description of the process. The kilns were closed by

walling over with lumps of chalk dug nearby; the unfired bricks were

placed above the chalk and a fire was lit in the two kiln pipes.

Large pieces of wood formed the base of the fire, to which were

added small bundles of twigs as well as furze, grass, moss and

bracken, and the fire would burn for three or four days.

Finally, when all had cooled, the bricks were covered with moss and

furze bound together and the kiln entrances were closed.

The bricks were finally removed, and the chalk then slaked with

water, causing it to powder. This was the lime used for mortar

and also to spread and improve the heavy clay agricultural land.

Certainly chalk was burned at Outwood for making slaked lime during

the first thirty years of the 19th century and there is no reason to

suppose methods had changed greatly.

The Outwood Kiln brickworks continued to prosper in a modest way.

Trade Directories of 1878 to 1882 list James Jones as proprietor;

1886 to 1890 Robert Jones; and 1894 Robert Williamson; and an advert

in the Bucks Herald, posted by Albert Ashby, of 6th May 1899

invites applicants for the job of brick-maker.

When supplies of suitable clay began to run short, some clay was

then dug at Broomfield Spring (where there are still holes to be

seen) on Northchurch Common, which was then carted to the kiln.

Until the outbreak of war in 1939 when the blackout prohibited the

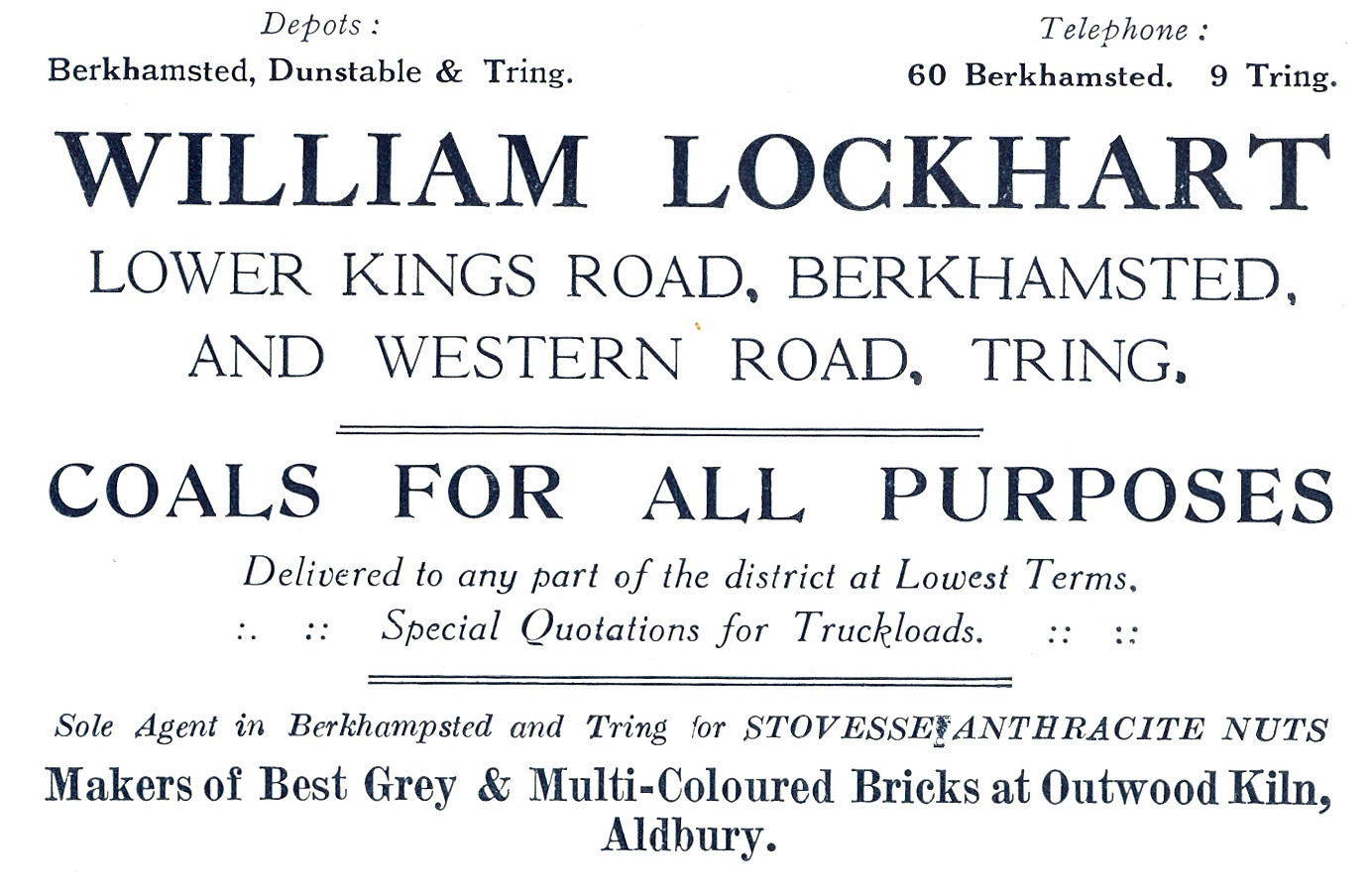

use of open-topped kilns, the brickyard was operated by Lockharts,

builders and coal merchants of Berkhamsted and Tring. In fact,

many local brickyards had to be ‘blacked out’ for the same reason,

and most did not reopen afterwards.

――――♦――――

5. BRICKMAKING – BUCKLAND COMMON

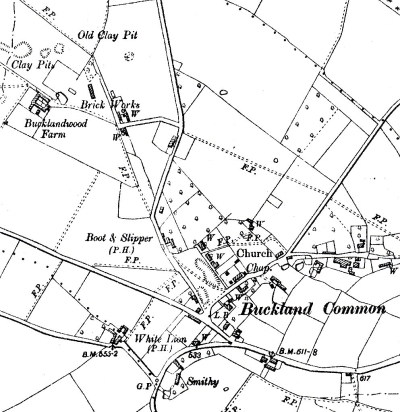

During the Victorian period, a number of small brickworks were

operating in east Buckinghamshire a few miles from Tring, most at

Buckland Common, where pockets of good clay were to be found.

The records are patchy, ownerships often changed, and the few

accounts can differ in date. But as far as can be discovered,

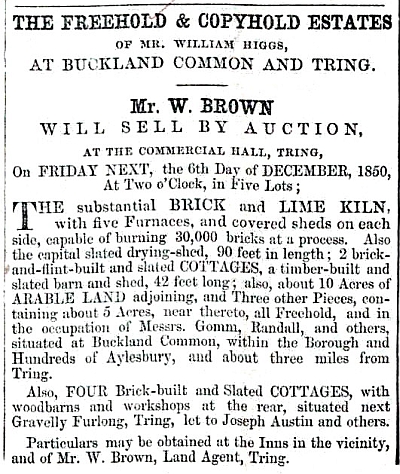

the first documented brick-maker is Job Brown; [1]

he is mentioned again in matters relating to the Inclosure of

Buckland Common in 1842, and is listed in trade directories in 1854.

|

|

|

Sale

notice for the estate of William Higgs |

When the

Rothschilds acquired the Tring Park estate, a brickworks was already

in situ on a portion of their land holdings on the Common, a yard

that produced hand-made multi-facing bricks in coal-fired Scotch

kilns. [2] The works were managed by George

Gomm of Buckland Wood Farm who appears in trade directories as a

farmer and brick-maker. Slightly nearer to Buckland Wood, a

second brickyard was sited in a field near Twye Cottages. In

1862 George Gomm is offering for sale “at his premises near The

Boot public house, 100,000 prime building bricks. The bricks

are all dry, of uniform size, of splendid colour and first-rate

quality.” The yard finally closed c.1899.

Three members of the Fincher family, John, Charles and Henry, Tring

builders and brick and tile makers, operated from the 1860s to 1961

making ordinary facing bricks and ‘specials’ (brickettes and

water-table bricks for window sills) in three Scotch kilns, also on

the Common at Cholesbury Lane Brickyard (opposite Chiltern

Cottages), using coal carted twice a day from Tring Station to fire

the kilns. As many as 1,000 bricks could be turned out on a

good day, and with work starting at 6 a.m., the brick-maker’s day

was a long one. The heyday of Finchers was the late Victorian

period when an advertisement appeared in the local paper “Wanted,

four good brick-makers. Apply Henry Fincher, Builder, Tring.”

A later advert appeared for a foreman brick-maker “to take

complete charge of brickyard, to dig clay, and make and burn bricks

at per thousand.” The firm constructed many public

buildings and private houses in and around Tring, including the

Church House in 1896, and the schoolroom at the rear of Akeman

Street Chapel, as well as Wigginton Village Hall.

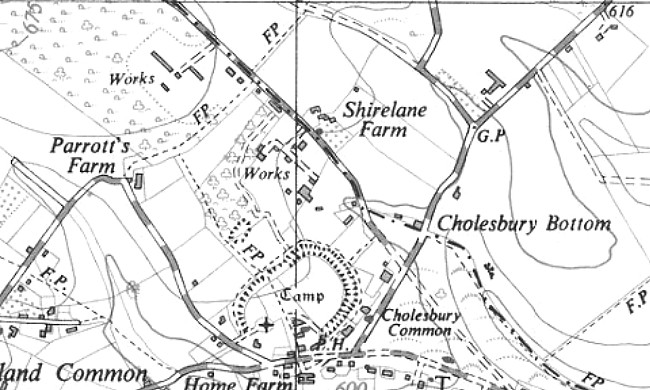

|

|

|

OS 1900

showing the brickworks at Buckland Common |

Over the years things did not always run smoothly at this yard.

In February 1909 Henry Fincher prosecuted one of his employees,

Frederick Penn, for the theft of 73 pounds of coal. The police

constable of Cholesbury discovered “black footprints leading from

the yard to the accused’s house, and coal stored in a sack in an

outside shed.”

The foreman at the time, George Dunton, appealed for leniency due to

the accused’s previous good character, and he was fined £1.

Later the firm was run by Henry Cook, and went into liquidation by

order of the Buckinghamshire County Court in 1935, following a

petition brought by Alfred Dunton, an employee who had sustained an

accident at work and been awarded a compensatory payment which had

been discontinued. He claimed that the company was unable to

pay its debts, an opinion with which the judge agreed. [3]

However, the Tring Brick Company did continue trading on the same

site until c.1960s.

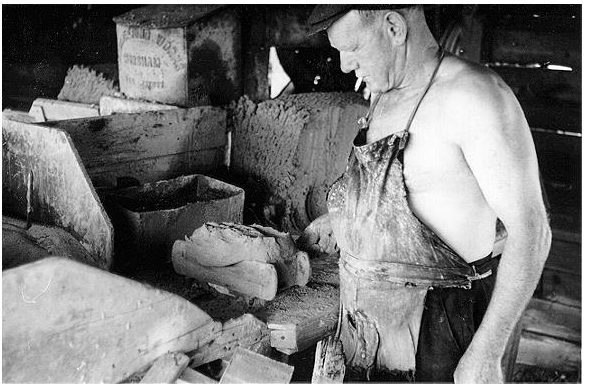

Moulding bricks at

Fincher’s

Brickworks, c.1960s

A short way out of the village, another firm of Tring builders,

Harrowell Brick Co. Ltd., operated in Oak Lane on a site of six to

seven acres. This works traded from c.1923 to c.1949 making

multi-facing bricks also in coal-fired Scotch kilns. During

WWII Fred Harrowell advertised in local papers, offering air raid

shelters constructed of either brick or concrete, suitable for six

to eight persons with construction within seven days, and at a price

of £34 each.

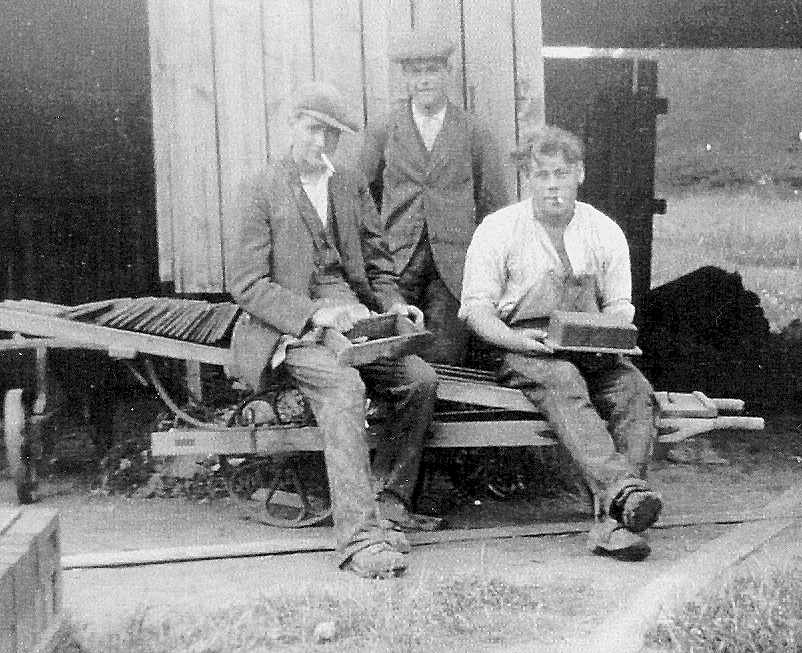

Harrowell’s

brick workers, Oak Lane, c.1930s

William Harrowell had founded the building business in the middle of

the Victorian period and the family also owned a brickworks at a

site in Shootersway, Berkhamsted. Many houses in the town are

constructed using Harrowells’ bricks moulded from the pockets of red

clay found in this area. [4] An anonymous

worker at this yard wrote an account of his hard-working days in the

1930s. [5] He describes digging the clay

from September to May; followed by cleaning out the pugging machines

[6] and the brick making tables, and ensuring

that the hacks [7] and covers were ready.

Four tons of the best coal was usually required for a burn, which

reached white heat towards the end of the firing process; he

commented that manoeuvring a loaded barrow filled with 120 bricks

down the ramp from the kiln took considerable skill, and laments

that the real craft involved in the brick-making process has been

lost due to mechanisation.

Chapter Notes

1. Index of Poll on 31.7.1839 for the Hundred of Aylesbury.

2. Scotch kiln – employing an up-draught which replaced the old

clamp firing method, thought to have been developed during the 17th

century when coal was used instead of wood or peat. Used by

small brickyards, these were open-topped chambers with six to ten

fire holes leading under a perforated floor into which the bricks

were stacked. After filling, the whole was covered with

loose-burnt bricks; firing taking from three to five days, with two

to three days of cooling. Capacity could be up to 80,000

bricks.

3. Bucks Herald archives July-September 1935.

4. The Berkhamsted Review, July 1996

5. Chesham Bricks, Keith Fletcher, pub.2005

6. Often a horse-drawn mill for mixing clay with other materials,

usually with a rotating blade.

7. Drying racks.

――――♦――――

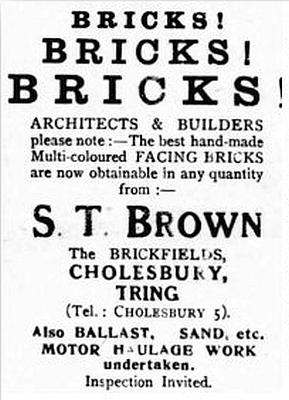

6. BRICKMAKING – CHOLESBURY and HASTOE

Cholesbury - Shire Lane

|

|

|

Sale of

bricks by Browns |

The demand for

housing after WWI led to the opening of S.T. Brown’s brickworks in

the 1920s on clay fields in Shire Lane. At its height, the

yard was producing 3 to 3.5m. bricks per year in coal-fired, and

later oil-fired, Scotch kilns.

This yard produced a number of different brick types, including

handmade facing bricks, and those known as ‘overburnts’ – meaning as

the name implies, overcooked bricks which are not impaired in

usefulness but making them less desirable commercially. Overburnts,

a large house built of these bricks and situated on Cholesbury

Common, was erected by the proprietor Samuel Thomas Brown (known as

Tom) as his own residence. A well known local figure, he died aged

96 and his obituary appeared in the Bucks Herald on 1st September

1950, describing a versatile man, who during the course of his life

had worked as a publican (licensee of the Rose & Crown, Buckland

Common), a farmer and pheasant breeder as well as a brick-maker. In

addition to his two farms, [1] Tom Brown acquired

a second brickfield at Hog Lane, Ashley Green, and also supplied

ballast, sand, and provided a motor haulage service. In 1938, the

old Buckland Wood Farm site was bought by Browns for its reserves of

clay. This business continued until c.1978 and the area is now

levelled.

‘Overburnts’

in 2016

Until 1937 six Dunton brothers, their father and three uncles all

worked at H. G. Matthews in Bellingdon. That same year saw the

opening of their own business on a six-acre site almost opposite,

specialising in the manufacture of handmade bricks, clay roof tiles,

gauged arches and fireplace brickettes; due to scarce capital

resources production entailed the use of a very crude kiln. Output

was doubled by 1939 but WWII put an end to further operations.

OS 1938 showing Brown’s

and Dunton’s

brickworks

After the war, when the acute shortage of housing created an

enormous demand for bricks, the Ministry of Works encouraged Dunton

Bros. to rent land in Drayton Wood, Shire Lane, on a site adjacent

site to Browns. At a UDC meeting in Tring in June 1946 the problem

was outlined when it was reported that the Ministry would not allow

the town’s proposed new council housing in Park Road to be

constructed using ‘facing’ bricks as specified by the architect, but

that plain flettons would have to do, possibly with a cream-coloured

render. The lack of progress on this Park Road site, due to the

post-war dearth of building materials, prompted the Council to send

a deputation to the Ministry of Works. [2]

Dunton Bros. traded at Shire Lane from 1946 to 1960; two cottages at

Longcroft located at the western end of the lane are built of bricks

from this yard, most traces of which have now gone but the old

workings provide a good home for local badgers.

In 1952 Duntons purchased 68 acres at Meadhams Farm, Ley Hill, for

seasonal brick production in two Scotch kilns. Some clay from here

was also taken to Shire Lane, and by the late 1950s weekly output

was 34,000 per week at Ley Hill and 40,000 at Cholesbury. After

several changes of ownership, and an increase to four kilns, the

firm was acquired by Michelmersh Brick & Tile Company, at that time

employing a high ratio of staff compared with other modern concerns,

as one third of the bricks were still moulded by hand. Due to

difficulties in the construction industry and to bad weather, the

closure of this smallest and oldest site in the group was announced

in 2013, when the area was then scheduled to become a waste dump.

Hastoe – Kiln Lane

A section of a map accompanying the sale particulars of the Tring

Park estate in 1872 marks exactly the site of the brickworks in Kiln

Lane, and an OS map of 1877 (below) confirms the location of clay

pits, kilns and pumps in High Scrubs wood at Hastoe. (Some 50 years

before then, a “brick-ground and cottage at Hastoe Cross, of just

over 15 acres in extent, and a rent of £11.5s.0d. p.a.” was

included in a previous sale of Tring Park estate; this possibly

refers to the same brickfield as that shown on the 1877 map but one

cannot be definite.)

OS 1877 showing brickworks

in Kiln Lane

|

|

|

Sale of

bricks by Alexander Parkes, Sept 1871 |

George Bull of

Oakengrove Farm in Shire Lane was the proprietor and is listed in

Kelly’s trade directories of 1860 to 1874. But he was operating

before these dates, as the invoice below records that he supplied

bricks to the Rothschild Aston Clinton estate in the late 1850s, at

a time when the mansion house was being enlarged and remodelled and

much building material was required.

Shortly before the acquisition of the Tring Park Estate by the

Rothschilds, sales of bricks from this area were arranged by

auctioneer and agent of the Estate, Alexander Parkes.

When Bull’s kiln closed is again difficult to establish, but as late

as 1891, the census return lists Charles Brown, brick-maker,

residing with his family at Hastoe Kiln. In WWII, local people

recollect pits in High Scrubs wood being filled in using student

labour. This action, reported in the Watford Observer of 1st March

1940, was taken seemingly because of considerable subsidence in the

wood, where trees had actually sunk in to large holes.

Record of bricks

bought from local suppliers by

Sir Antony de

Rothschild

Chapter

Notes

1. During WWII brickmaking became low priority, so Tom Brown

reverted to farming and acquired the 154-acre Buckland Wood Farm

opposite one of the defunct Buckland Common brickfields. This

farm was sold at auction when the Tring Park estate was broken up.

2. One of these gentlemen was Councillor Harrowell, a Tring builder

and brick-maker (see Buckland Common section).

――――♦――――

7. BRICKMAKING – WIGGINTON

In the Victorian period, members of the Honour family had diverse

business concerns in or near Tring. These included building,

brickmaking, undertaking and horticulture. Their brickmaking

operation was centred in Chesham Road, Wigginton, where clay was dug

from a small pit, which was abandoned when exhausted, and another

then hollowed out. The site and pits are shown on the map

below:

Map showing location of brickyard in Chesham Road

Among many local buildings constructed by Honours and probably using

their own bricks, are two picture palaces, one in Chesham and old

The Empire in Akeman Street, Tring, which is the last of the town’s

three purpose-built cinemas still standing, the premises having been

put to various uses since closure in the 1930s. Honour’s also built

a house in Chesham Road to accommodate their own family, almost

opposite to the brickyard and known as Netherby Grange.

A second and earlier brickworks in this area was owned by Thomas

Little. a well-known local farmer of the 433-acre Tring Grange Farm;

the clay pits and brickyard were situated in Roundhill Wood, on the

Chesham to Cholesbury road. An account in the Bucks Herald of 1840

stated “last Saturday, a notorious character named Joseph Cox,

was committed for two months hard labour for damaging the brick kiln

belonging to Mr Thomas Little of Tring Grange Farm.” Thomas

Little evidently prospered, as eleven years later the census for

Wigginton shows him employing 16 men on the farm, and another nine

in brickmaking.

Receipt for

bricks from Thomas Little to

Sir Anthony de Rothschild

Thomas Little appears to have ceased trading in bricks in 1885, when

the stock of bricks, together with all the tools and utensils

connected in manufacture, were offered for sale. After giving up

Tring Grange Farm, Thomas Little retired, took himself off around

the world, and intended to start a well-boring irrigation business

in Queensland which he proposed to name ‘Tring’.[1] But he met a sad

end, possibly due to his very short sightedness, by walking into the

‘death-trap’ near Brisbane [2] and was drowned.

However, two years before Thomas Little ceased farming, James Honour

is listed in the Tring Park Estate account books as renting

‘brick-ground, kiln etc. at Tring Grange’. It is also likely that

James Honour took over the works in Kiln Lane, Hastoe, following the

departure of George Bull c.1878, but just who owned what and when in

the Wigginton area is rather difficult to pin down.

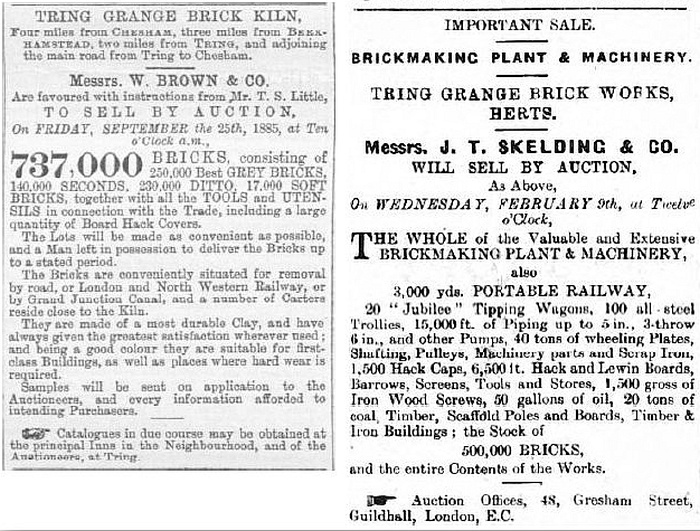

Sale of bricks by Thomas Little, 25th September 1885

Closure of Tring Grange Brickworks

Chapter

Notes

1. From the writings of Tring historian, Arthur Macdonald, c.1890.

2. Storm water drainage systems beneath the city.

――――♦――――

8. OTHER LOCAL BRICKYARDS

Wendover

Never known as a brickmaking area, there is a reference in 1688/9 to

a brick kiln on Birche’s Peece. [1] In the

Militia List of 1798 for the town, Nathaniel Winfield is listed as a

brick-maker, although exactly where he worked is not known.

Aston Clinton

A Rate Book of 1862 lists an area of over two acres comprising

brickyards, kiln, sheds and meadow at Normill Terrace, Aston

Clinton, but no other details. Nearer to Aylesbury another

brickworks owned by the Bonham family is documented; [2]

this operated from c.1864 at Broughton-cum-Bierton on a site now

covered with large ponds. The company, then known as W & G

Bonham, was dissolved in 1887. [3] This may

not have been too disastrous because, like many businessmen in the

Victorian period, George Bonham had many strings to his bow, as he

is described as grocer, baker, brick-maker and post master.

Berkhamsted

That bricks were produced in the Berkhamsted area for probably

hundreds of years is evidenced by the name of ‘Brickhill Green’ at

the top of the town on the south side. A medieval pottery

existed at nearby Potten End [4] where many years

later a brickworks was established. In the early 19th century,

John Hare Nash occupied four acres, comprising a cottage, garden,

woods and a brickyard. How he fired his kilns is something of

mystery, as the Ashridge Steward of the time had forbidden him to

cut furze, the traditional fuel, the reason being so much was

already being taken by owners of kilns at Coldharbour, Aldbury,

Kensworth, and Ivinghoe. Nash may have ignored the ban, or

used wood from his own land; in any case, this operation continued

for almost a hundred years employing four men and three boys.

John Nash’s son expanded the business and increased the workforce by

four men, until he retired and sold his plot to a nurseryman.

A local competitor was Daniel Norris at Little Heath, who advertised

in the local press “bricks of all kinds.” Both yards closed

at the about the same time at the end of the century.

The 1833 London & Birmingham Railway Act had stipulated that the

line was not to deviate from the authorised route when passing

through the grounds of the Norman Castle (probably the first

instance of what we would now call a ‘preservation order’), no

structures, except for necessary bridges, culverts etc., were

to be built, neither was the Company permitted to make bricks or

burn lime anywhere within the parish.

Some 30 years later, on the opposite side of the valley, according

to local historian, the late Percy Birtchnell, “kilns were a

familiar sight on the skyline in 1863”, and these kilns operated

for another hundred years making bricks on the upper part of Bell

Lane and Darrs Lane. According to the particulars of sale for

the Rossway Estate “The freehold property and brick and lime

works with two kilns and drying sheds, plus three cottages, gardens,

barns, stables, cowhouse comprise over 14 acres and are in

occupation of John Skinner.” In 1883 John Howard is listed

in the Pigot’s Directory as a brick-maker at Woodcock Hill,

Northchurch. Brickmaking continued in Shootersway until well

into the next century in a yard operated by Charles Harrowell [see

Buckland Common section].

Ivinghoe

A specialised activity peculiar to the immediate area, was the

short-lived industry of digging for coprolites. [5

and 6] On land in Ivinghoe Parish owned by Earl Brownlow

and rented to Thomas Gale, a seam was discovered in the late 18th

century, and several sites were worked until the late 1870s; where

clay lay beneath the fossil bed, this was sometimes combined with

brickmaking. [7] Another tenant farmer on

the estate, Richard Burdett of Horton, also received licence for

coprolite digging on his fields, and later turned to brickmaking. [8]

The coprolite industry most likely was almost finished by the time

Foxons set up the Ivinghoe and Horton Brick & Tile Company in 1877;

the following year an advertisement appeared in the Bucks Herald

“a Good Sand Stock Brick-maker – apply at Ivinghoe and Horton

Brick Yard.” But no mention is made of the coprolite trade

in a directory six years later when Jasper Foxon is shown as working

as foreman at the brickworks. He is followed after two years

and until 1920 by Thomas Foxon listed as brick-maker in what was a

small yard producing yellow-coloured bricks; these were used in the

construction of several buildings in Ivinghoe village. On OS

maps from 1877 onwards the brickfield is marked on the B488 road as

‘Old Kiln’. The company was dissolved c.1932 [9] and the site

is now occupied by a bungalow.

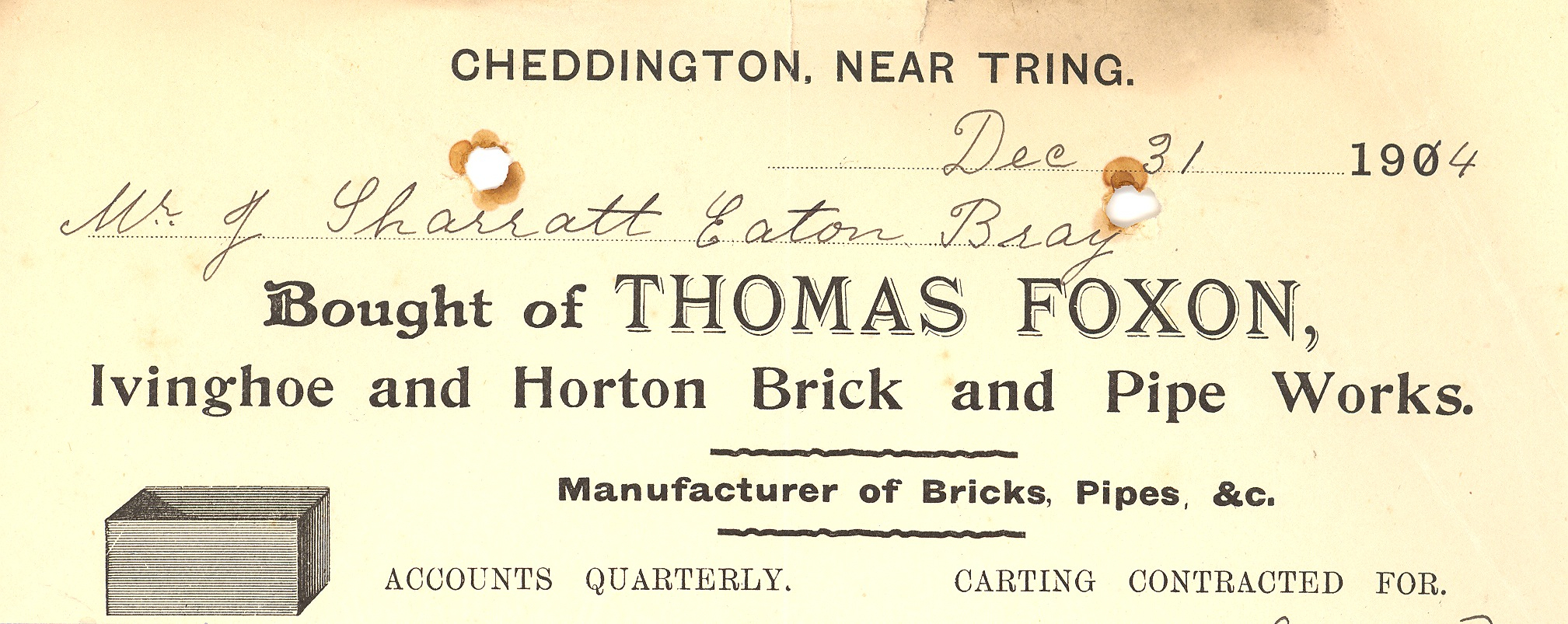

Invoice

heading from Foxons of Ivinghoe

Bellingdon

The only local brickfield still in business but a little outside the

immediate area of Tring is H. G. Matthews founded at Lye Green in

1923; their operation at Bellingdon near Chesham followed shortly

afterwards. At the peak of the industry, 23 brickfields were

operating within a radius of Chesham, but this has now dwindled to

three, mainly due to lack of new deposits of clay, although the firm

of Matthews owns 1,000 acres. A policy of careful restoration

on the site of old workings is always maintained.

The firm continues to produce half a million high-class bricks of

different types each year from clay found in the original deposits

both at Bellingdon and Chalfont St Giles, although clay can now be

dug at greater depths than in the old days. Bricks are moulded

both by hand and by machine, and a tour round the yard gives some

idea of the old ways of brick making and the firing of kilns, two

kilns burning wood which produces a greyish-coloured brick, the

final colour depending upon the firing temperature. Up to

1,000 moulds of different shapes are held in stock, some having been

acquired from the closure of nearby Duntons (see Cholesbury

section).

Digging clay by hand

with windlass winch

Matthews’ brickworks, 1924

Matthews’ bricks have been used in several National Trust

properties, as well as at Hampton Court, Chequers, Chesham clock

tower, and Tesco stores at Tring and Amersham. Always known for the

support given to the local community, Matthews donated the materials

to extend Cholesbury Cricket Clubhouse and St Leonards Village Hall.

Marsworth/Cheddington

During the soil excavations necessary during the building of the

Grand Junction Canal, the Resident Engineer, James Barnes, was able

to report [10]:

“In the Summit

at Tring, a part of the canal is executing in the parishes of

Marsworth and Cheddington, where plenty of good clay is found in the

cutting for the purpose of making bricks; my present object for

beginning there was to dig clay this winter ready for making a

sufficient quantity of bricks next summer that will be found

necessary for carrying on the works in this quarter. . . .”

Making bricks

by hand at Matthews, 2016

Six months later, Barnes was again reporting “. . . ..about one

million bricks are made, and nine moulders are constantly employed.

. . .” He then goes on to say that he would put this to

good use by making bricks that were needed for the northern section

of the canal, [11] a measure which would save

considerably on transportation costs; it is reasonable to assume

that these bricks may have been used in the construction of the many

hump-backed bridges leading from Tring to its satellite villages,

but no trace of these canal-side brick-workings has been discovered.

Modern Manufacture

Apart from H. G. Matthews at Bellingdon, none of the brickworks

described in this section survive and workers at those old yards

probably would not recognise today’s methods of manufacture.

Digging and mixing of the clay is highly mechanised, and the early

line and drag machines have generally been replaced by excavators.

Ingredients such as sand, water and anthracite are added

mechanically to the clay before crushing to ensure the right

consistency for easier moulding. Moulded bricks are dried

using gas before being transferred to oil-fired Scotch kilns where

they are fired at higher temperatures for less time than previously.

Chapter

Notes

1. Calendar of Deeds, 1941, Bucks Record Society 5.69.

2. Bucks County Council, ID 0104500000, Monument.

3. Centre for Buckinhamshire Studies, ref. D/HJ/4/1/1.

4. A History of Potten End, Vivienne J M Bryant, pub.1986.

5 and 6. Gazetteer of Buckinghamshire Brickfields, Andrew

Pike, pub.1980:

‘Coprolites’, from the Greek meaning ‘stone’ and ‘dung’, are

fossilised dinosaur droppings, found in the Ivinghoe/Slapton area in

the greensand overlying chalk marl and gault clay. When ground up,

coprolites could be converted into superphosphate for supply to

fertiliser manufacturers.

7. Buckinghamshire Historic Towns Assessment Report, 2012.

8. Kelly’s Directory 1887.

9. National Archives, ref. BT34/179/11256.

10. Report by James Barnes to the General Committee at a meeting on

7th 1797.

11. Marsworth in Living Memory, Carole Fulbrook Hawkins, pub.

c.1997.

――――♦――――

9.

METALWORKING

In Tring throughout the 19th century many craftsmen working with

metal traded in different parts of the town. Not all were using

heavy metal, and their descriptions vary from Iron Founder, Brazier,

Tin-men, Whitesmith, Bell-hanger, Ironmonger, Blacksmith and Farrier.

Sometimes they advertised other specialist craft skills as well,

such as Cooper, Wheelwright and, by 1902, Cycle Agent. Some of the

larger concerns over the years are described below.

G. Grace & Son

The present-day letter heading of G. Grace & Son proclaim that it is

the oldest established family business in Tring, being founded in

Frogmore Street by Sebastian Grace in 1750 (a busy man who married

two wives and sired 18 children). As well as metal working and

ironmongery, at different times members of the Grace family traded

as blacksmiths, whitesmiths, gunsmiths, gasfitters and bell-hangers,

and later pioneered the early motor industry in Tring. In the

mid-19th century Charles Grace located to 29 Akeman Street where he

worked with one apprentice, and then to 34 High Street; it was his

son Gilbert who built the present premises. With its distinctive

wrought-iron balcony, the High Street shop has been a familiar landmark since

built in 1890 to a design by local architect William Huckvale.

The garage workshops behind specializes in

repairing and servicing classic cars.

Grace’s

Ironmongery at 68 High Street

At the end of the Victorian period, Graces were advertising as

constructional ironworkers, and examples of their skill can be seen

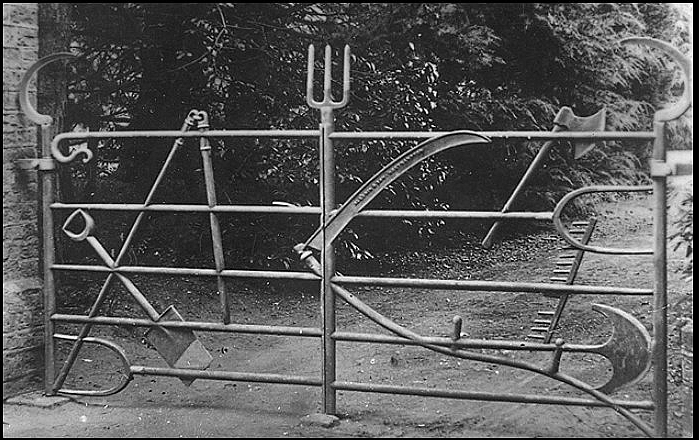

in different locations around the town. One particular local

curiosity is what is known as the ‘Implement Gate’, made for a

member of the Mead flour-milling family, and for many years sited

opposite the firm’s main entrance in New Mill. The gate has since been

restored and removed to a site in Marsworth.

The Implement Gate

Work for the Rothschild family on the private waterworks and central

heating system at Mentmore Towers led to further commissions and to

the supply of materials for their mansion houses both in Aston Clinton

and Tring Park.

Gilbert Grace, the present proprietor of the business and grandson of

the first Gilbert, gives some interesting details of activities at

the firm. The whitesmith plied his craft in what was referred to as

‘the Tin Room’ and this included the re-lining of saucepans and

other types of utensils. The old blacksmith’s shop with its five

forges, situated at the rear of the premises, was burnt out in a

blaze in 1994, thus destroying a reminder of Tring’s heritage. Some

of the metal work manufactured in the forges include the clock face

on the tower of the parish church; and fine large examples can also

been seen in the Zoological Museum in Akeman Street. Before the

Museum was

built c.1889, Walter Rothschild took a trip to Paris accompanied by

Gilbert Grace, who had been commissioned to erect the roof structure.

The purpose of the visit was to gather ideas by viewing the

newly-built Eiffel Tower; the result can be seen by looking high

above the top floor showcases. Other decorative features in the

museum manufactured by Graces include the railings around the

galleries and on the stairways.

Gates made at

Grace’s premises - entrance drive to Tring Park mansion

|

|

|

Gilbert

Grace on the staircase of the

Zoological Museum, 1992 |

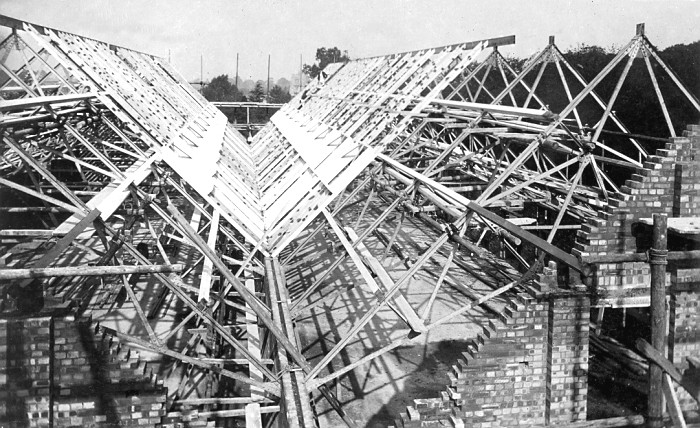

Later, c.1909, a large extension was erected on the east side of the

Museum to house the enormous and growing collection of

insects and to provide more space for bird specimens. The end

result was a group of buildings around three sides of a quadrangle,

the whole presenting a very attractive aspect from Park Street. Graces of Tring again supplied ironwork for the construction of the

roof.

Crawley Bros.

In 1839 William Crawley appears in a Tring trade directory operating in Akeman Street as a wheelwright. By 1850 he

had moved to Western Road on the site of what was the motor

garage of Wright & Wright. In addition to his trade of wheelwright

he also worked as an iron-founder, at that time employing four men and

a boy. Joseph Budd, a Tring local historian, writes that “the

Crawley ironworks was mainly agricultural and industrial

blacksmithing and forging, but not horseshoeing, which was done by

the various farriers scattered about the town.”

Crawley’s premises were sited immediately adjacent to those of

carriage builder George Parrott who had established his business in

1870, and this proximity no doubt proved beneficial to both

businesses.

The third generation of Crawleys, brothers Herbert and Henry,

commenced trading on their own account in Frogmore Street in the

1880s, and then took over their father’s firm three years before his

death. After that, matters did not go well, mainly due to

under-capitalisation followed by the break-up of their partnership.

Roof

construction on the extension to Tring Museum, c.1909

Like so many small ventures of this type, craftsmen do not always

make good businessmen and the arrival of the motor car meant a

decline in the trade of the wheelwright. Herbert Crawley ran

the business at a loss until 1900 when he had to admit defeat

with an appearance in the Aylesbury Bankruptcy Court before the Official

Receiver. There he gave a full and candid account of his situation [1]

explaining that he “kept a ledger for debtors, but not a bought

ledger for creditors. He used to keep a slate on which he wrote the

orders, and did not keep any other book except this ledger and the

slate. He never prepared any statement with the object of showing

what his income and expenditure was, neither did he take stock ……”

Unsurprisingly this old-established Tring firm was wound up

and ceased trading shortly afterwards.

Herbert Crawley outside his house in Western Road

(Parrott’s carriage works on left)

The Crawleys’ neighbour, George Parrott the coachbuilder, retired

and as the garage premises of Wright & Wright were expanding, the

Crawley house was demolished, the outbuildings modernised or

replaced, and the redundant chimney which served the steam-driven

engines also disappeared.

Tring Iron Works

The history of the Hillsdon family in Tring is rather convoluted. John Hillsdon senior was born in Waddesdon in 1805. Twenty years

later he and his wife and five children were living at Gamnel Wharf where

he worked as a miller. By 1850, Tring trade directories list both

John and his son John junior trading as millwrights. In 1861

they are described as ‘agricultural machine makers’, manufacturing

at premises on the corner of Chapel and King Streets in a house and

yard. Today this is a private residence known as

‘The Steam House’.

‘The Steam House’ on the

corner of Chapel and King Street

OS 1877 showing

Hillsdons’ premises

At this time their business did not prosper and both were declared

bankrupt in the sum of £587.14s.0d. They were imprisoned for

debt, languishing in the House of Correction and County Gaol in

Hertford.

But their assets were sold to pay the debts and later trading was

resumed. By 1869 John junior was able to display a comprehensive

entry in Kelly’s Directory, being described as an engineer,

millwright, iron and brass founder, manufacturer of portable and

fixed steam engines, water wheels, corn, bone and colour mills. John

junior and his family emigrated to New Zealand but his brother,

George, carried on the business after their father retired and it

is likely that he made the engine installed in the Wendover

windmill. [2] In 1855 [3] the firm erected a new windmill at Quainton.

They also worked on the silk mill in Tring and possibly both the

windmills at Goldfield and Waddesdon, but the best-known surviving

example of their work is sited on Hawridge Common. This tower

mill has recently been (cosmetically) restored with a refurbished cap and

fantail, a new set of sails, and its exterior has been lime-washed

in white. Now a private house with a

colourful past, [4] the present owners have taken care to respect

the mill’s Grade II listing.

A recent picture of

Hawridge tower mill

A slender tower mill, built in 1883, it was erected by the firm at

what was considered the reasonable price of £300. Replacing the old

smock mill that stood on the same site, some use was made of

existing materials, including ironwork and one pair of sweeps (i.e.

framework for the sails). Hillsdons did not construct the

machinery inside the cap, but probably carried out the installation;

one account states that until a tenant could be found in 1885, being

experiences millers they worked the mill themselves.

After serving the town and surrounding area for 80 years, Tring

Ironworks finally closed down c.1905.

Towards the end of the 19th century a third John Hillson, who may

have been from another branch of the same family, took over the

premises of Charles Grace (see above) at 29 Akeman Street. Shown as

a coach and ironsmith, stationer and fancy warehouseman, it was

not long before he moved to Western Road working simply as a

coach-smith, all mention of ‘iron’ being gone. It is likely that he

was employed in the nearby carriage-building business of George

Parrott, later the motor garage Wright & Wright.

William Tompkins

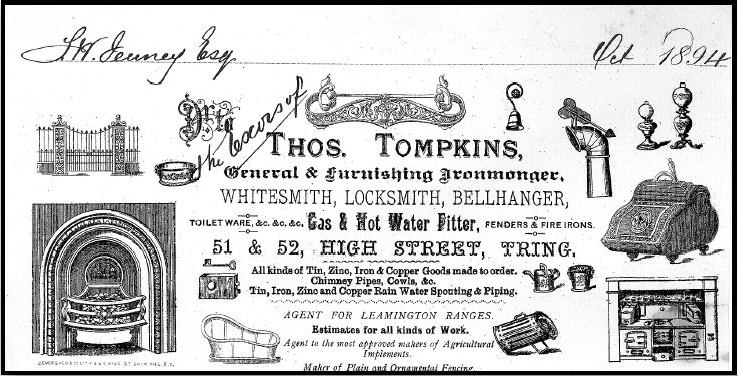

On the site of the present excellent hardware store of F. W. Metcalfe

& Son, William Tompkins established a business c.1820s, proclaiming

himself an ironmonger and brazier. In those years when

diversification of business interests was common, by 1839 William

and Martha Tompkins were also listed as bakers. This activity

probably arose due to the great influx of labourers (i.e.

navvies) working on the construction of the nearby London &

Birmingham Railway, and Tompkins knew that his shop was the nearest

to the site of their work on the great Tring cutting. He also

supplied the tools necessary for these tough men, as well as

provisions which were referred to by the workers as their ‘tommy’. In the cellar below the present shop, now the area for sales of

kitchen equipment, are well-preserved heavy oven doors set into the

brickwork; the fire beneath vented under the ground emerging outside

the shop frontage, and one wonders what better way to tempt passing

customers into the premises than the aroma of freshly baking bread.

Bread oven in

the basement of Metcalfe’s hardware store, 2016

Two more generations of Tompkins carried on trading, firstly Mrs

Mary Tompkins & Sons who advertised as wholesale and retail

ironmongers, as well as coppersmiths, braziers, tin, iron and zinc

plate workers; stove-grates and ranges were also manufactured on the

premises. One son Thomas took over, and when he died in 1894 his

business was acquired by William and Arthur Dawe, who also had works

in Akeman Street; these brothers moved with the times as among their

varied activities they advertised as cycle agents.

Thomas Tompkins

invoice heading (now Metcalf’s

hardware store)

After a period serving as a motor garage and, in WWII, a Royal Navy

land-ship where barrage balloons and kites were constructed, the

premises once again in 1948 reverted to its original use, that of

retail hardware, a business that three generations of the Metcalfe

family have run since.

Hampshire & Oakley Ltd.

After World War II, Rotherham man H. C. Hampshire, tired of the grime

and smoke, was seeking to escape to the country, but England was

still recovering from five years of upheaval and suitable premises

were hard to find. After a two-year search, an opportunity arose to

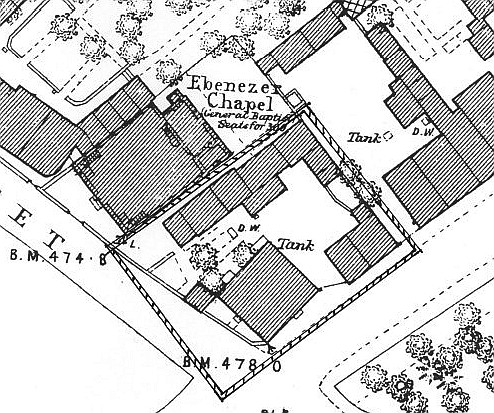

acquire the disused Ebenezer Chapel at the top of Chapel Street,

Tring, (Incidentally, this building was immediately next to the old

Tring Ironworks).

Wishing to expand, their hobby of ornamental ironwork developed into

a sound business concern. The firm grew and was soon producing many

types of iron and steel items from wrought-iron gates, lamp

standards, trolleys, and even the framework for a Dutch barn. When

Hampshire died in 1954, Thomas Moy, one of his employees known as

‘Tom the Blacksmith’, took over as leading hand. He made the altar

rails for St Martha’s church immediately opposite the premises, and

the arch over the gates of Tring Memorial Gardens. He left Hampshire

& Oakley in 1962 to become the blacksmith at the Tunnel Cement Works

at Pitstone and, in addition to his normal work, he fashioned the

iron fittings for the restoration of Pitstone Windmill.

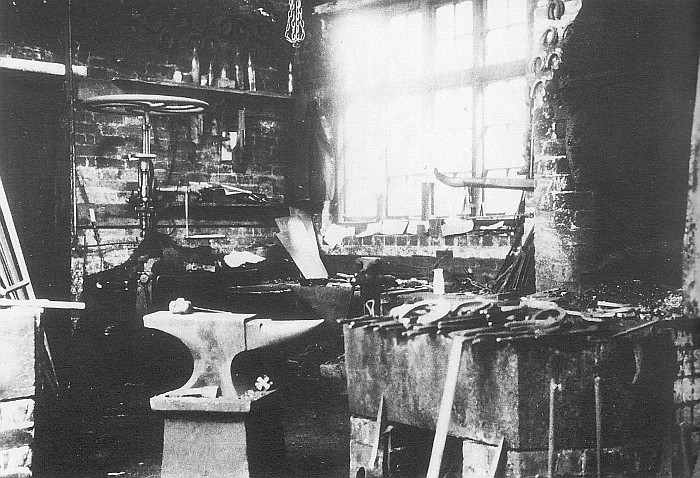

Wishing to return to the original trade of his Sheffield days of

spring-making, also led Hampshire to a decision to acquire a

300-year old forge in Akeman Street [below],

for the manufacture and repair of leaf springs for cars and lorries. A modern gas furnace was installed to produce the intense heat

required for the silicomanganese steel needed in the process, but a

few of the old fitments were retained as a reminder of the functions

carried out by those who had wrought iron and shod horses. [5]

After the closure of Hampshire & Oakley in 1970, the old chapel was

used by a company carrying out plastic injection moulding, but is

now demolished and a modern house occupies the site.

Tring Forge

|

|

|

Entrance

to Harrow yard and

Tring Forge, c.1890 |

From medieval times or earlier a market town like Tring must have

had blacksmiths and farriers plying these essential trades, but the

earliest mention is not until c.1820 when trade directories list

three individuals, as well as one each in Wigginton, Aldbury and

Wilstone.

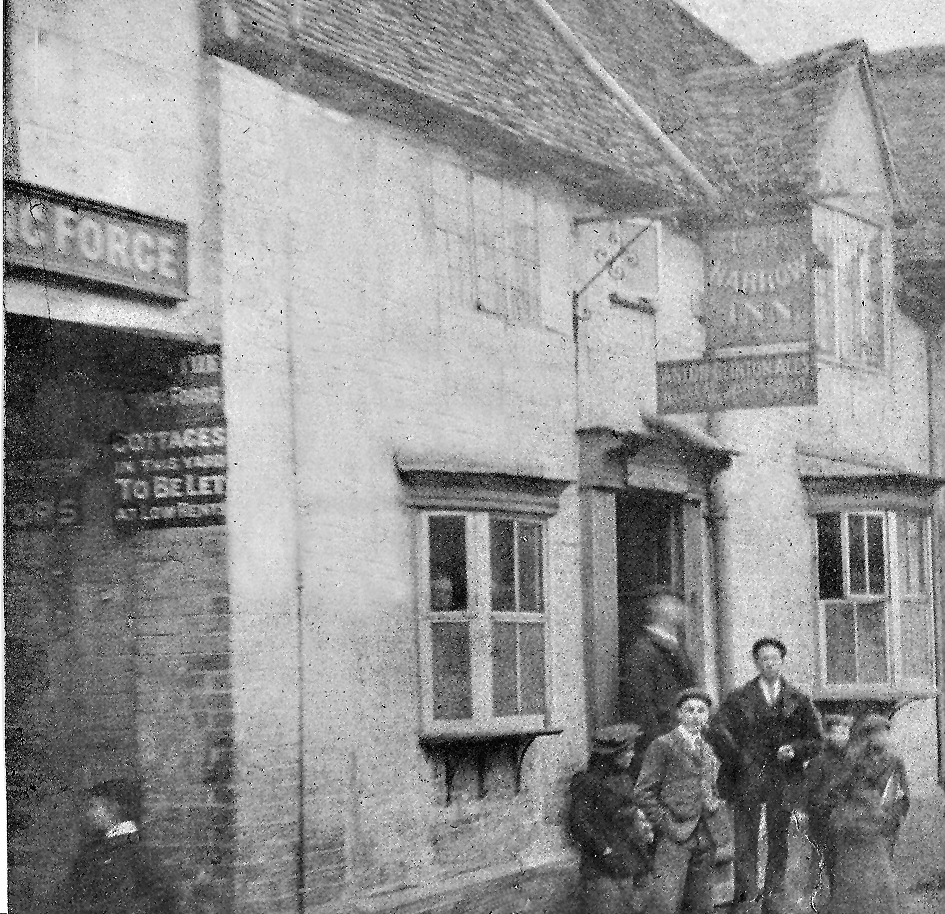

The particulars of an auction sale in 1863 of The Harrow pub in

Akeman Street show a blacksmith’s forge in the yard, and this is

marked as a large smithy on OS map dated 1877. These premises were

most likely those used by Hampshire, and over the preceding years

were worked by various proprietors – including at the turn of the

century, Daniel Lines, and before WWII by Frederick Cooper.

This old forge and the other premises in the stable yard of The

Harrow pub were finally demolished in 2006 to make way for new

houses.

Forge at the Bulbourne Works

An attractive Grade II listed group of buildings stands on the Grand

Union Canal at Bulbourne Tring, near the junction with the Wendover

Arm. At first the site was simply a maintenance yard but in 1847 it

was decided that it would be less expensive if lock gates were built

near where they were needed. At Bulbourne a workshop was set up in

the open air, and in 1903 the present buildings were erected. Originally a team of blacksmiths manufactured all the mechanical

parts for the gates, but as time went on modern machinery enabled

the process to be carried out more quickly, and the forge was used

only occasionally.

The premises of

‘Hammer & Tongs’, 2015.

The site has since been redeveloped as residential accommodation

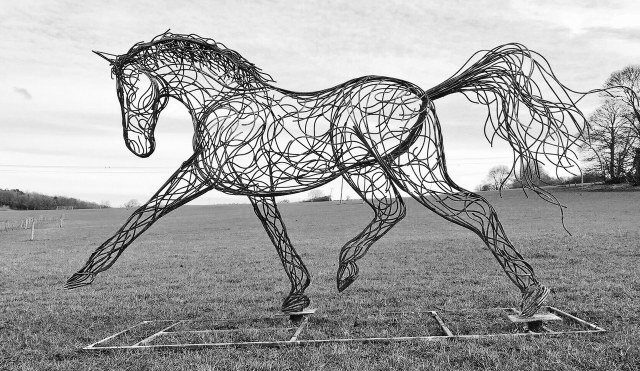

However, with the closure of the Bulbourne Works in 2004, the forge

area then again was worked in a traditional way, as Hammer & Tongs,

established in 1988 by master blacksmith Paul Elliott, supported a

group of blacksmith artists using traditional skills to work on

commissions of any size for architects, local authorities and

individuals. As well as items such as railings, balconies and gates,

artwork was produced in both wrought and cast iron, including garden

furniture and water features. Some of the pieces were displayed

outside the old premises, and made an attractive waterside feature

when viewed from the canal or opposite towpath. At the time of

writing, there are plans to develop the Bulbourne workshops site,

including the Grade II listed buildings, for housing.

The Tring Park Stud

Always interested in agricultural matters, and anxious to improve

the stock on both his tenant and local farms, Lord Rothschild set up

a Stud Farm in Duckmore Lane,

Tring, where working Shire horses were bred, stabled and cared for. Among the various new outbuildings set around the large cobbled yard

was a blacksmith’s shop equipped with the whole range of necessary

tools, a soft wooden floor for horses to stand on whilst being shod,

and a manger to keep them preoccupied. Adjoining the forge were a

tool storage area and an engine house with brick chimney.

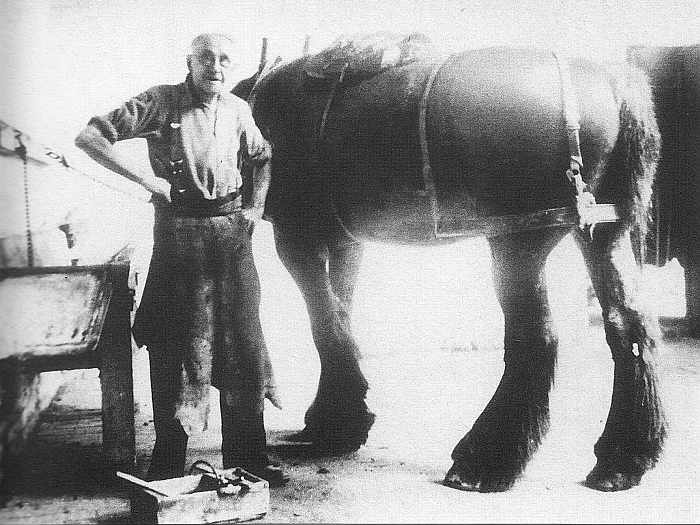

A blacksmith from Lancashshire, Albert Christopher, was employed as

shoe smith, and it was generally acknowledged among the local

farming fraternity that Bert, as he was known, had a special ‘knack’

with horses. It was claimed that many would only be shod by him, and

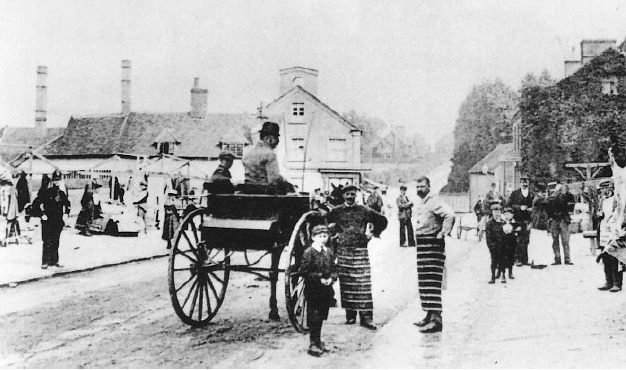

in fact he travelled round the area, as well as much further afield